Not many people would be able to answer this question.

What exactly is “Ermine a Lozenge Argent charged with three Blackbirds rising proper on a Chief Gules an open Book also proper garnished Or between two Ducal Coronets of the last.” ?

Well, it’s one of these, more or less. What’s a lozenge between friends?:

The origin of the High School’s coat of arms has always been, to me, a major enigma. Apparently, there has always supposed to have been a connection between the arms of Dame Agnes’ family, namely “Mellers” and another family called Mellor, who lived in Mellor, a village between Stockport and Glossop.

(Where?)

(Well, let’s put it this way. in either town you can easily get a bus to Manchester. It’s a distance of some seven miles and twelve miles respectively)

Here is their coat of arms:

To me though there is quite a difference in spelling between Mellor and Mellers, although the Mellor coat of arms is obviously a reasonable fit with the school’s crest.

This theory, though, does rely almost totally on the supposition that Richard Mellers was related to this “Family in the North” whose coat of arms displayed three black birds. In actual fact, there is no reason to suppose any proven link whatsoever between the two families. After all, it’s a very long way between Nottingham and Stockport in late medieval times. More than ninety miles, in fact. The best part of a week on foot, not counting any unexpected meetings with Robin Hood and his Merrie Men.

Let’s look at a small number of other likely coats of arms. Let’s start with Mellers. It should be said that Dame Agnes herself always spelt her name as “Mellers” (but never as “Mellor”):

For “Mellers”, we find very few coats of arms, but there is this one:

Let’s try “Meller”. We do find this one, and furthermore, the very same shield is listed elsewhere as “Mellers” :

That’s not the answer, though,, because we also find this shield for Meller, as well:

That’s not the answer, though,, because we also find this shield for Meller, as well:

And this one:

And this one:

Clearly, something, somewhere, is not quite right. It may even be very wrong. There are problems here, and the first major one may well be connected with the simple issue of the spelling of Dame Agnes’ surname. Despite her own insistence on Mellers, mentioned above, a quick look at “Google Images” will reveal that Mellers, Mellor, Meller and probably Mellors, appear to be disturbingly interchangeable.Coats of arms just seem to come and go. They are different every tine you look at Google. This is because, I suspect, they are connected less with accurate heraldry than the desire to sell tee-shirts, mugs, key rings, ties and even underpants with your family crest on them.

Those black birds on the High School shield have always been regarded as Blackbirds, an everyday bird species in England:

The theory is that the heraldic word for a blackbird is “merle”, taken from the French, and this gives us a devilishly funny pun for the surname “Mellers”. Such side splitters are called “Canting Arms”. They are used to establish a visual pun, as in the following examples:

I am just not sure about this word “merle”. Just because a coat of arms contains a number of black birds (as opposed to green ones), that does not automatically mean that we are dealing with canting arms, even if the French word “merle” refers to our familiar back garden bird, the Blackbird, aka turdus merula, and the name “Mellers” sounds perhaps, possibly, maybe, slightly, conceivably, like it.

What is more disturbing, though, is the discovery that “merle” appears to mean absolutely nothing whatsoever in English Heraldry. On Amazon, the search for “Heraldry” reveals five books, all with the same title. It is “A Complete Guide to Heraldry” by A.C.Fox-Davis:

This rather old book is the standard work on English Heraldry and has been for quite a considerable time. It is a book of some 645 pages, but there is not a single “merle” on any one of them. And more important still, if merles did actually exist in Heraldry, then why did the Heralds’ College, known also as the College of Arms, call these birds “blackbirds” when they made that formal grant-of-arms to the school as recently as 1949? Why didn’t they call them “merles” and thereby preserve the “Laugh, I nearly died” visual pun?

This rather old book is the standard work on English Heraldry and has been for quite a considerable time. It is a book of some 645 pages, but there is not a single “merle” on any one of them. And more important still, if merles did actually exist in Heraldry, then why did the Heralds’ College, known also as the College of Arms, call these birds “blackbirds” when they made that formal grant-of-arms to the school as recently as 1949? Why didn’t they call them “merles” and thereby preserve the “Laugh, I nearly died” visual pun?

And don’t think that the College of Arms are just a bunch of fly-by-night door-to-door sellers of heraldic key rings and underwear. They were founded well before Dame Agnes Mellers, in fact as far back as 1484. To quote the definition on the Heraldry Society website:

“The College of Arms is the only official English authority for confirming the correctness of armorial ensigns — Arms, Crests, Supporters and Badges — claimed by descent from an armigerous ancestor, or for granting new ones to those who qualify for them.”

In other words, if they say it’s a blackbird it’s a blackbird. You can’t just decide to call it a “merle” because you feel like it, or because it seemed like a good idea at the time. It’s just not allowed. Here is another blackbird, just to refresh your memory:

In 1920 at least, nobody called it a “merle”. In June of that year, the new school magazine, “The Highvite” contained a “Sports Chorus”, including appropriately vigorous music. The words were…

“Score our High School / ye Highvites now score for victory.

Our High School / For Highvites, never, never, never shall be beaten

By any Worksop / Newark & c. team

At the Sign of the Blackbirds three.”

No “merles” there then. It is equally interesting to note that in “The Nottinghamian” of December 1921, the school’s emblem is again referred to as containing blackbirds, rather than merles. This overturning of tradition, however, does not mean that the use of three black birds does not connect us directly with Dame Agnes. Let’s look at it from a different angle, just for a moment.

Many people have believed over the years that it was only when the school changed its site from Stoney Street to Arboretum Street in 1867 that the three black birds were first adapted. But this was definitely not the case since photographs from the mid-nineteenth century show quite clearly that a badge with three birds was displayed on the wall of the Free School building. In this case, though, their wings were folded rather than the modern version, flapping and ready for immediate and dynamic intellectual and sporting take-off:

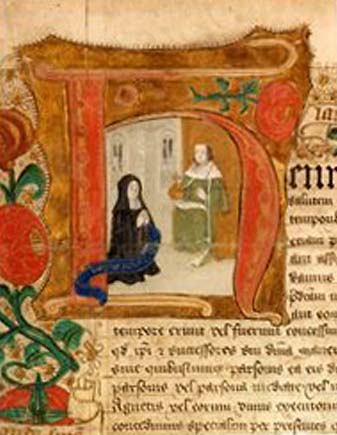

Indeed, it is thought that the three black birds were in evidence as an unofficial badge for the school from at least June 16th 1808 onwards. On this date, an unknown but apparently very bored clerk has decorated the title page of the funky new volume of the Schoolwardens’ Annual Balance Sheets with the traditional three black birds, so it has clearly been known as a symbol connected with the school for a very long time.

Interestingly enough, another slightly more modern place where the birds’ wings can be seen as folded dates from 1936, when some new stained glass sections were put into the windows at the back of the recently built Assembly Hall:

And nowadays, of course, this folded wings version forms the badge of the Old Nottinghamians’ Society. Presumably, that is why they appear in this guise on a car badge being sold off on ebay:

Next time, I will attempt to answer the question of where did those black birds come from? In the meantime here’s a clue. Not all black birds are Blackbirds: