Recently, we looked at the impoverished life of Mary Anning, a self taught young woman who would eventually outrank the top palaeontologists of Europe. Here she is, with her dog, Tray:

During an incredibly hard life, Mary was oppressed for two things she couldn’t help.

She was a working class woman. As a woman, she could not vote, she could not hold public office, and she could not attend university. Most importantly, she could not join the Geological Society or even attend their meetings. As a member of the working class, she should in theory have been a farm labourer, a worker in a big mansion or in a factory. Here are some jobs that were thought suitable for a young working class woman:

For me, that kind of prejudice is both shocking and unacceptable. But her troubles had only just started.

As a working class woman, whenever she discovered a new type of dinosaur, only the rich man who bought the fossil was allowed to write about it officially in a scientific journal.

After years of major discoveries, none of which had ever been properly credited to her, her friend, Anna Maria Pinney, wrote that:

“The world has used her ill. Men of learning have sucked her brains, and made a great deal (of prestige and money) by publishing works, of which she furnished the contents, while she derived none of the advantages.”

And, of course, Ms Pinney was right.

Secondly, Mary was poor. Her father died leaving debts rather than an inheritance. The family were forced to live on parish relief and a certain amount of upper class patronage. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch, a wealthy Lincolnshire collector was extremely upset by Mary’s poverty. He sold his own collection of fossils in 1820 to help Mary and her family. The latter received a generous proportion of the £400 received (c £40,000 today).

When geologist Henry De la Beche painted “Duria Antiquior”, a picture of prehistoric life, he used fossils Mary had dug up and he gave her the money he made from his sales to help the family. This was the first ever picture of what they called then “Deep Time” :

Mary died on March 9th 1847 from breast cancer. Her life now began to fascinate people more and more.

In “All the Year Round” edited by Charles Dickens, one of the many authors said that:

“the carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.”

It is frequently mooted that she was the real person in the tongue twister:

“She sells seashells on the seashore,

The shells she sells are seashells, I’m sure

So if she sells seashells on the seashore

Then I’m sure she sells seashore shells.”

Sadly there is no evidence whatsoever for this connection, beyond the circumstantial. And this is, of course, the very best kind of evidence and so the theory is therefore almost certainly true.

In 2010, the 350th anniversary of the Royal Society, this august body published a list of “the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science”. It is sad how few of them ordinary people will have heard of, even though their work was, in many cases, ground-breaking. You can find it here.

And here’s that top ten of women scientists:

Anne McLaren (1927-2007)

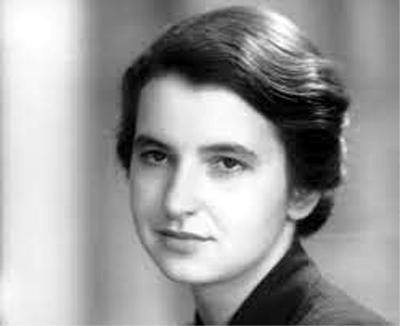

Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958)

Dorothy Hodgkin (1910-1994)

Elsie Widdowson (1908-2000)

Kathleen Lonsdale (1903-1971)

Hertha Ayrton (1854-1923)

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917)

Mary Anning (1799-1847)

Mary Somerville (1780-1872)

Caroline Herschel (1750-1848)

Most people, myself included, don’t have any idea who these women were or what they did. Follow the link above, or just try googling some of them, and you’ll soon see to what extent they were the victims of prejudice.

Rosalind Franklin was perhaps the saddest. She died from ovarian cancer at the age of 37, four years before Crick, Watson and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962 for their work on DNA. Rosalind was unable to receive the prize, as Nobel Prizes cannot be awarded posthumously, but she received no mention in the acceptance speeches.

I found the full story on this website:

“Maurice Wilkins, assistant director of the King’s College, London biophysics lab, secured a particularly pure sample of calf thymus DNA. Rosalind Franklin’s team carried out crystallographic studies of this DNA.

Using x-ray equipment and a micro-camera, Rosalind Franklin and graduate student Raymond Gosling photographed and analyzed these samples of DNA. In May 1952, they took a ground-breaking photo, labelled #51, which provided the clearest diffraction image of DNA and its helical pattern so far.

It was this photo, alongside her precise analysis of the x-ray diffraction data, that inspired Crick and Watson to move away from their initial idea of a three-helix molecule and make the necessary calculations to develop the double helix model of the DNA strand we now know.”

Here is Picture 51:

I certainly feel that Mary Anning should have a statue here and there, and perhaps Rosalind Franklin deserves one or two as well.