I have already mentioned in a previous blog post that my Grandfather, Will Knifton, emigrated to Canada in an unknown year before the Great War. Conceivably, he was with his elder brother, John Knifton, or more likely perhaps, John went across the Atlantic first and then Will joined him later on. I have only two pieces of evidence to go on.

Firstly, it is recorded that a John Knifton landed in Canada on May 9th 1907. His ship was the “Lake Manitoba” and he was twenty three years of age. His nationality is listed in the Canadian records as English.

On the other hand, I still have an old Bible belonging to my Grandfather, which says inside the front cover,

“the Teachers and Scholars of the Wesleyan Sunday School, Church Gresley, given to him as a token of appreciation for services rendered to the above School, and with sincerest wishes for his future happiness and prosperity. March 26th 1911.”

Whatever the truth of his arrival, Will lived at 266, Symington Avenue, Toronto. He then worked as a locomotive fireman on the Canadian Pacific Railways, between Chapleau, Ontario, right across the Great Plains to Winnipeg. He also talked many times of the town of Moose Jaw, although he never supplied any details that I can remember:

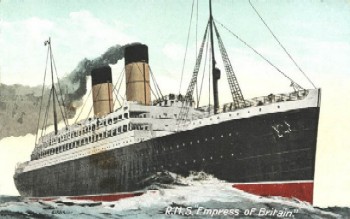

Will joined the Canadian Army on June 12th 1916 at the Toronto Recruiting Depôt. He sailed from Canada for the Western Front on July 16th 1916 on the “S.S.Empress of Britain”:

For many years, Will had courted a local English girl called Fanny Smith, the daughter of Levi Smith, a labourer in a clay hole in the area around the village of Woodville, in South Derbyshire, where they all lived. Will wrote to her from Canada and then, during his time in the army, he sent her regular postcards from France. During his leaves from the front, he always returned to see her and they married on July 15th 1917:

I still have quite a few of Will’s postcards. He had clearly bought this postcard just before he left Canada for England and the Great War:

He used to speak enthusiastically about Montreal and especially about the famous Hôtel Frontenac:

On July 25th, Will duly arrived in England, and was taken on strength into the army at Shorncliffe in Kent. He posted his postcard of Montreal soon after he arrived at Shorncliffe Camp in Folkestone, Kent, at 7.00 pm on July 27th 1916. Here is the back of it:

The message reads:

“Englands shores Dearest, arrived safely on the Empress of Britain, a pleasant voyage was free from sickness will write you later fondest love Will”.

Notice how Will is beginning to become a Canadian with his unusual lack of a preposition in “will write you later”.

Shorncliffe Camp was where Will, and many other young men, were to train for France and the Western Front. Having mentioned the idea of being sick in his previous postcard, Will continues the romantic mood with a picture of the men and horses of the Canadian Field Artillery drilling hard on the parade ground:

The reverse is here:

Will manages to make a charming juxtaposition of “men and horses at drill with the big guns” and “Fondest thoughts” to his true love. (And she really was his true love.)

Will began his training at Shorncliffe on July 27th and he remained there until November 17th 1916. The schedule for basic training makes interesting reading nowadays. This particular week was the one ending June 5th 1915, and it is difficult to imagine that Will would have done anything substantially different just over a year later:

Monday

(6.30-7.00 am) Squad drill without arms

(8.00-9.00 am) Physical Training

(9.00-9.30 am) Bayonet Fighting

(9.30-10.00 am) Rapid loading

(10.00-12.00 am) Company Training

afternoon as for morning less ½ hour squad drill

Tuesday

morning as for Monday

afternoon Entrenching (2 Companies), remainder as for Monday

Night March

Wednesday

morning as for Monday

afternoon Entrenching (2 Companies), remainder as for Monday

Thursday all day Battalion field training

Friday

morning as for Monday

afternoon as for Monday

Saturday

morning as for Monday, less afternoon (holiday)

(If this were a restaurant, you would only go there once, wouldn’t you?)

Will’s next postcard continues the hearts and flowers theme with a photograph of the men’s tents.

Will’s own tent is marked with a cross:

This is the reverse side of this postcard. Firstly, as Fanny received it:

And here is the message enlarged:

Will remained at Shorncliffe until November 17th. He sent his girlfriend, or perhaps by now, his fiancée, some more post cards before he left. We will look at them in the near future.