I have already mentioned in a previous blog post that my Grandfather, Will Knifton, emigrated to Canada in an unknown year before the Great War. Conceivably, he was with his elder brother, John Knifton, or more likely perhaps, John went across the Atlantic first and then Will joined him later on. I have only two pieces of evidence to go on.

Firstly, it is recorded that a John Knifton landed in Canada on May 9th 1907. His ship was the “Lake Manitoba” and he was twenty three years of age. His nationality is listed in the Canadian records as English.

On the other hand, I still have an old Bible belonging to my Grandfather, which says inside the front cover,

“the Teachers and Scholars of the Wesleyan Sunday School, Church Gresley, given to him as a token of appreciation for services rendered to the above School, and with sincerest wishes for his future happiness and prosperity. March 26th 1911.”

Whatever the truth of his arrival, Will lived at 266, Symington Avenue, Toronto. He then worked as a locomotive fireman on the Canadian Pacific Railways, between Chapleau, Ontario, right across the Great Plains to Winnipeg. He also talked many times of the town of Moose Jaw, although he never supplied any details that I can remember:

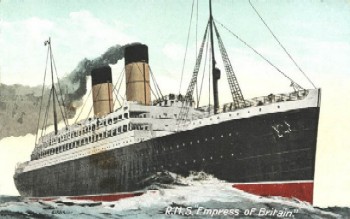

Will joined the Canadian Army on June 12th 1916 at the Toronto Recruiting Depôt. He sailed from Canada for the Western Front on July 16th 1916 on the “S.S.Empress of Britain”:

For many years, Will had courted a local English girl called Fanny Smith, the daughter of Levi Smith, a labourer in a clay hole in the area around the village of Woodville, in South Derbyshire, where they all lived. Will wrote to her from Canada and then, during his time in the army, he sent her regular postcards from France. During his leaves from the front, he always returned to see her and they married on July 15th 1917:

I still have quite a few of Will’s postcards. He had clearly bought this postcard just before he left Canada for England and the Great War:

He used to speak enthusiastically about Montreal and especially about the famous Hôtel Frontenac:

On July 25th, Will duly arrived in England, and was taken on strength into the army at Shorncliffe in Kent. He posted his postcard of Montreal soon after he arrived at Shorncliffe Camp in Folkestone, Kent, at 7.00 pm on July 27th 1916. Here is the back of it:

The message reads:

“Englands shores Dearest, arrived safely on the Empress of Britain, a pleasant voyage was free from sickness will write you later fondest love Will”.

Notice how Will is beginning to become a Canadian with his unusual lack of a preposition in “will write you later”.

Shorncliffe Camp was where Will, and many other young men, were to train for France and the Western Front. Having mentioned the idea of being sick in his previous postcard, Will continues the romantic mood with a picture of the men and horses of the Canadian Field Artillery drilling hard on the parade ground:

The reverse is here:

Will manages to make a charming juxtaposition of “men and horses at drill with the big guns” and “Fondest thoughts” to his true love. (And she really was his true love.)

Will began his training at Shorncliffe on July 27th and he remained there until November 17th 1916. The schedule for basic training makes interesting reading nowadays. This particular week was the one ending June 5th 1915, and it is difficult to imagine that Will would have done anything substantially different just over a year later:

Monday

(6.30-7.00 am) Squad drill without arms

(8.00-9.00 am) Physical Training

(9.00-9.30 am) Bayonet Fighting

(9.30-10.00 am) Rapid loading

(10.00-12.00 am) Company Training

afternoon as for morning less ½ hour squad drill

Tuesday

morning as for Monday

afternoon Entrenching (2 Companies), remainder as for Monday

Night March

Wednesday

morning as for Monday

afternoon Entrenching (2 Companies), remainder as for Monday

Thursday all day Battalion field training

Friday

morning as for Monday

afternoon as for Monday

Saturday

morning as for Monday, less afternoon (holiday)

(If this were a restaurant, you would only go there once, wouldn’t you?)

Will’s next postcard continues the hearts and flowers theme with a photograph of the men’s tents.

Will’s own tent is marked with a cross:

This is the reverse side of this postcard. Firstly, as Fanny received it:

And here is the message enlarged:

Will remained at Shorncliffe until November 17th. He sent his girlfriend, or perhaps by now, his fiancée, some more post cards before he left. We will look at them in the near future.

Shorncliffe is still there and I believe still a barracks. I often pass that way when I’m Kent.

I didn’t realise it was still there. It must have trained hundreds of thousands of soldiers in a century.

Yes indeed if only its wall could

Talk.

That hotel has such a Bavarian feel to it. Fascinating story thank you for sharing

And thank you for passing by!

Fantastic post, John! Wow. The postcards are primary sources and say a lot about soldiers preparing for the Great War. The Canadian perspective is interesting to me! “With fondest Love” Did he end up marrying Miss Fanny? Oh, I hope he wasn’t killed in the war and had a long life ahead of him.

Yes, Will married Fanny in 1917, returned to the war but survived to return home to his wife. They were married for 63 years and died within days of each other, Fanny remaining blissfully unaware that Will had passed on. I will be doing a second blog post about the rest of Will’s war career in the near future.

An odd coincidence but my paternal grandfather’s brother, Arthur, also emigrated to Canada around 1910/11 and lived in Sydenham St., Toronto. You grandfather must have lived within a couple of miles of my great-uncle. Was there a large migration from Britain to Canada at this time?

I think there must have been. Perhaps people were getting fed up with the exploitation of the Industrial Revolution, and wanted to start new lives, in a new country, without all the restrictions and limitations of a class driven society like England. Thanks a lot, by the way, for your interest!

I agree John.

I missed that one John!

To be absolutely honest, so did I. But I’m sure it’s in there somewhere!

Reblogged this on Lest We Forget and commented:

The sequel…

Thanks very much!

Your grandparents still live through your stories John.

Thank you. It’s strange how much I think about my Grandad. I would love to spend a day with him sometime soon, old man with old man.

Montreal in 1910

Thank you, That is a photograph of wonderful quality. My Grandad seemed to be very fond of the place.

This might be of interest

http://www3.onf.ca/ww1../prologue.php

Thanks, I will look through it. As you are so aware, Canada, and indeed Australia and New Zealand, tend to be the forgotten partners in the World Wars.

Especially this

http://www3.onf.ca/ww1../apres-guerre-film.php?id=531545

Ces archives, tournées en France ou en Angleterre, décrivent la démobilisation massive qui a suivi l’Armistice de novembre 1918. La première scène se déroule dans un dépôt de libération, où des blessés montent dans une ambulance militaire, tandis que des hommes leur font au revoir de la main. Puis, dans un autre lieu, des hommes chargent des sacs d’équipement dans un camion. Une troisième séquence montre des soldats qui embarquent sur un navire. Dans la dernière partie, filmée depuis le pont du bateau, on voit une longue file de membres du personnel militaire, dont des infirmières, qui montent à bord.

Avec la démobilisation, 250 000 Canadiens devaient être rapatriés. La tâche en elle-même était imposante. D’autres facteurs sont venus la compliquer.

Premièrement, les opinions divergeaient sur la façon de ramener les Forces canadiennes au pays. Le général Currie favorisait un retour des troupes par unités. Malgré son côté pratique, l’approche entrait en conflit avec le principe selon lequel les volontaires qui étaient partis les premiers pour le front devaient avoir la priorité sur les conscrits plus récents. Mais la stratégie de Currie a prévalu. Les autorités espéraient que le maintien des unités permettrait aux officiers des classes moyennes de mieux maîtriser les soldats de la classe ouvrière. Car, dans les jours qui ont suivi l’Armistice, l’esprit du « Un pour tous et tous pour un », qui avait régné durant les combats, risquait de céder le pas à une conscience de classes qui divise les troupes.

Deuxièmement, la pénurie de bateaux ralentissait le rapatriement. Non seulement, il n’y avait pas suffisamment de navires, mais nombre d’entre eux étaient mal équipés pour la tâche. Les mauvaises conditions vécues par les soldats lors de leur retour sur le S. S. Northland avaient provoqué un scandale et entraîné la création d’une commission d’enquête visant à imposer des normes minimales pour le transport des troupes. L’objectif de la commission était louable, mais il a entraîné encore plus de retards. De plus, les liaisons ferroviaires à partir de Halifax et de Saint John, les seuls ports qui n’étaient pas bloqués par les glaces, ne convenaient pas au déplacement de l’immense nombre de soldats attendus.

Au même moment, en Grande-Bretagne, des pénuries d’essence et des conflits ouvriers ralentissaient le trafic dans les ports, ce qui rendait la situation encore plus difficile au cours d’un hiver particulièrement froid. Épuisés par la guerre, les Canadiens devaient attendre dans des camps où la discipline se relâchait et l’impatience prenait le dessus. La colère a atteint un sommet en mars 1919, quand les soldats ont appris que la 3e division, qui regroupait de nombreux conscrits, était en train de s’embarquer à Liverpool. Cette nouvelle a provoqué des émeutes au camp de Kinmel Park. Cinq hommes ont été tués et vingt-cinq blessés. La révolte a fait l’objet de nouvelles à sensation dans la presse britannique. Bien que des problèmes disciplinaires semblables se soient produits dans les troupes britanniques, certains journaux anglais ont publié des reportages sur des « Canadiens devenus fous », faisant un lien entre les troubles et le nouveau spectre du bolchévisme.

L’événement a provoqué un refroidissement temporaire des relations entre le Canada et la Grande-Bretagne, mais il a eu pour effet d’accélérer le rapatriement. En mars 1919, plus de 40 000 Canadiens ont été ramenés au pays, ce qui représentait une augmentation importante par rapport au mois précédent, où ils avaient été seulement 15 243 à rentrer. Au 1er avril, 110 384 soldats et 17 000 personnes à charge avaient quitté l’Europe. En avril, une grève des débardeurs a créé des retards, mais, en août, il ne restait que 13 000 Canadiens environ en Angleterre.

C’est sir Albert Edward Kemp qui a assumé la responsabilité de superviser la démobilisation des Canadiens. Ce fabricant prospère de Toronto avait été nommé président du Comité des achats de guerre, en 1915. Par la suite, il a remplacé Sam Hughes comme ministre de la Milice. En 1917, il a été envoyé en Angleterre en tant que ministre des Forces militaires outre-mer et il a fait partie du Cabinet impérial de guerre. À tort ou à raison, c’est Kemp et son état-major qui ont été principalement blâmés pour le scandale du S.S. Northland et les autres problèmes causés par la démobilisation, même s’il est généralement admis qu’ils ont fait un bon travail dans les circonstances.

Si j’ai le temps, j’essaierai de visiter le lien que vous m’avez donné. Il y a quelques années nous sommes allés en vacances au Pays de Galles et nous avons interrompu notre voyage en visitant l’église énorme et blanche de Kinmel pour voir les tombeaux de ces pauvres jeunes canediens, exilés pour jamais dans un pays qui ne semblait pas être reconnaissant de leur sacrifice.