Last time, I finished by mentioning how the regiments of the Zulu army were distinguished by differently coloured shields and the number of marks on them. Shields might be brown, white or black and might have black spots, brown spots, white spots or no spots at all. Here’s a display in a South African museum:

It occurred quite frequently that the Zulus would use the captured shields of their enemies as a ruse, causing confusion or even panic among the ranks of their adversaries. Chaka actually owned his own army’s warshields, the isihlangu, and they were handed out only in times of war. Men were punished for losing them.

Years later, when the Zulus were fighting the Boers, Bongoza, a General in the Zulu army of King Dingane, even showed his men how to hide behind their shields and pretend to be grazing cattle.

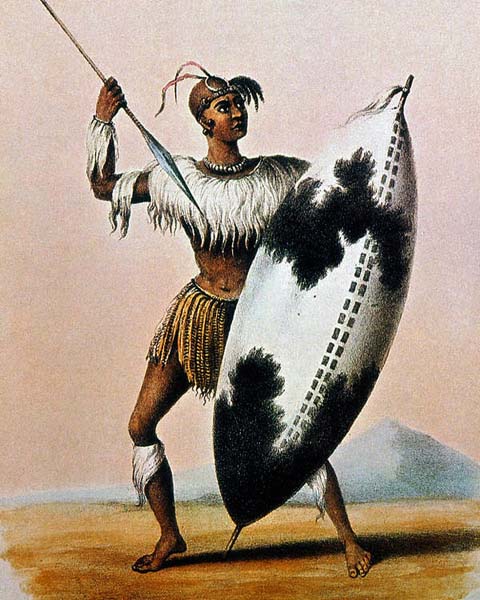

Funnily enough, that was actually the only innovative idea that I came across that did not come from Chaka, the most brilliant military thinker ever in sub-Saharan Africa. I found this coloured version of what is usually a black and white illustration of him on the internet:

Chaka was the one, for example, who changed his men’s diet, having them consume a fairly constant mixture of beef and cereal porridge. The existence of a new, fitter, stronger, army, would, of course, ultimately create more wars, but at the same time it would allow free access to further supplies of beef and cereals from the territories of the conquered tribes.

I don’t know if this dietary régime really did keep the Zulus leaner, fitter and more able to march long distances but that was the widely held belief among non-Zulus in Natal and Zululand in the 19th century. The problem, of course, was that the Zulus themselves left no written accounts and that all we have to go on are the accounts of one or two white traders such as Francis Farewell and Henry Fynn. And any books written by men who merely want to make money, of course, tend to exaggerate, just to make even more money.

For that reason, we shall never know for certain just how bloodthirsty and crazy Chaka was after his mother, Nandi, died on October 10th 1827. Did he really order every Zulu mother-to-be to be executed? Did he really seek out more than 7,000 people who were not sufficiently grief stricken and have them all killed? And even more crazily, did he really have every cow with a calf to be killed so that their offspring would all know exactly what it felt like when your mother died?

Only written records from an unbiased source can tell us such things. We are, for the same reason, still unsure about how far a Zulu regiment, an impi, could run in a day. In 1879 the whites firmly believed that the answer to that question was FIFTY miles. It is even quoted in the film “Zulu”.

Modern Zulus, especially the politicians, wear spotless, bright, white trainers. Their followers frequently wear very brightly coloured jeans and carry golf umbrellas :

Some other aspects of bygone Zulu life we do know about through photographs. Across the world, many kings wear crowns. Zulu kings were slightly different and we have photographs from the nineteenth century to prove it. Here is King Cetshwayo:

He is wearing an “isiCoco”, an emblem of rank in pre-colonial days, meaning variously “the king”, “married man” or “warrior”, depending on the person wearing it. It was originally made from a mixture of beeswax, charcoal and snake skin, the latter being a symbol of African royalty and kingship. Warriors would wear leopard skin, because that was the animal they usually hunted. Nowadays, the isiCoco is made more easily, perhaps, by twisting a fibre ring into the hair. The ring has been covered in charcoal and gum and then polished with beeswax.

One final Zulu speciality weapon was the “knobkerrie”, a type of club with a large knob at one end. It can be thrown at the enemy like a javelin, or at animals while out hunting, or it can be used to club an enemy at close quarters. Sometimes it was used in stick fights as young boys practiced their combat techniques. In the Zulu language, it is called an “iwisa” and nowadays is not considered a weapon.

I have always been fascinated by the Zulus. As a little boy, I was an avid reader of books by H Rider Haggard. It began when “Allan Quartermain” was given to me as a Christmas present, and then I bought “King Solomon’s Mines” and “She” with my pocket money. I was entranced by the heroic Zulu warrior, Umslopogaas, who appears in “Allan Quartermain” and in its sequel “Nada the Lily” a book unique in the nineteenth century in that all of its characters are black. Absolutely remarkable for that era.

I even tried to learn some Zulu phrases, but I never really had the chance to use the phrase “Kill the white wizards” so I soon forgot it. In actual fact, the only one I do still remember is “Amba gachlé ” which means “Go in peace”. Not a bad phrase to be the only one you know.

Here’s Umslopogaas :