On February 17th 2021, I published a blog post about one of my Dad’s favourite poems, “Flannan Isle”, by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, which was written in 1912. The poem concerned the mysterious disappearance of the three lighthouse keepers in December 1900. This strange incident has never been explained once and for all, and I was asked for my own ideas by a number of different people. Unfortunately, the subject proved so complex that I was unable to do it justice in fewer than four blog posts, although, on the other hand, I would argue that all four are as interesting as any that I have ever written.

So here we go……..

At midnight on December 15th, the steamship Archtor, nearing the end of its voyage from Philadelphia to Leith, passed the Flannan Isle lighthouse which was not showing a light. Instead of two quick bursts of light every 30 seconds, there was just darkness. Captain Holman, however, was unable to report this fact to the Northern Lighthouse Board, because the Archtor continued its voyage, but ran aground in the Firth of Forth. The NLB, therefore, were unaware of the situation until their own supply ship, the Hesperus, made its usual regular visit to the lighthouse on December 26th. The Master of the Hesperus, Captain Harvie, at the first opportunity, sent a telegram to the NLB. The significant elements can be read below:

“The three Keepers, Ducat, Marshall and the occasional have disappeared from the island. On our arrival there this afternoon no sign of life was to be seen on the Island. Fired a rocket but, as no response was made, managed to land Moore, who went up to the Station but found no Keepers there. The signs indicated that the accident must have happened about a week ago.”

The “occasional” was a temporary replacement for a full time lighthouseman who was ill. His name was Donald McArthur. Donald was due to be replaced by Joseph Moore, the third Assistant Lighthouseman allocated to Flannan Isle, now recovered from his illness. Joseph was on board the Hesperus and Captain Harvie sent him ashore to search the island. Captain Harvie then reported to the NLB the two key things that Joseph found during his search of the lighthouse and the island….

“…. The clocks were all stopped and other signs indicated that the accident must have happened about a week ago.”

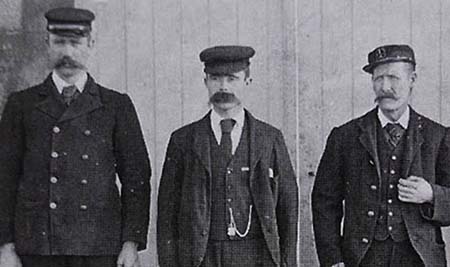

Here’s Joseph Moore:

Joseph Moore also wrote his own letter to the NLB though, about what he had seen during his search of the island:

“On coming to the entrance gate I found it closed. I made for the entrance door leading to the kitchen and store room, found it also closed and the door inside that, but the kitchen door itself was open………..

On entering the kitchen I looked at the fireplace and saw that the fire was not lighted for some days. I then entered the rooms in succession, found the beds empty just as they left them in the early morning.”

And………

“Mr McCormack and myself proceeded to the lightroom where everything was in proper order. The lamp was cleaned. The fountain full. Blinds on the windows etc.”

The island is so small that it could be searched in a very short time…..

“We traversed the Island from end to end but still nothing to be seen to convince us how it happened. Nothing appears touched at East Landing to show that they were taken from there. Ropes are all in their respective places in the shelter, just as they were left after the relief on the 7th.”

Both sides of the island were not the same though….

“On the West side it is somewhat different. We had an old box halfway up the railway for holding West Landing mooring ropes and tackle, and it has gone. Some of the ropes, it appears, got washed out of it, they lie strewn on the rocks near the crane. The crane itself is safe.

The iron railings along the passage connecting the railway with the footpath to the landing and started from their foundation and broken in several places (sic), also railing round crane, and handrail for making mooring rope fast for boat, is entirely carried away.”

Joseph Moore could also work out how the men were dressed…….

“Now there is nothing to give us an indication that it was there the poor men lost their lives, only that Mr Marshall has his seaboots on and oilskins, also Mr Ducat has his seaboots on. He had no oilskin, only an old waterproof coat, and that is away. Donald McArthur has his wearing coat left behind him which shows, as far as I know, that he went out in shirt sleeves. He never used any other coat on previous occasions, only the one I am referring to.”

Some of the evidence above is important. To end this blog post, I will write out some of the things discovered by the NLB and perhaps you can have a think about what they prove, or, indeed, disprove……..

The clocks were stopped

The entrance gate I found …..closed

The entrance door ….. found it closed and the door inside (as well)

The kitchen door itself was open

The fire was not lighted for some days

I found the beds empty just as they left them in the early morning

In the lightroom everything was in proper order. The lamp was cleaned. The fountain full. Blinds on the windows etc

Nothing appears touched at East Landing

Ropes are all in their places

And then there is that huge contrast:

On the West side……… old box halfway up the railway ….has gone……the ropes…… got washed out of it, they lie strewn on the rocks.

The iron railings …….with the footpath to the landing …….started from their foundation and broken in several places…..railing round crane, and handrail for making mooring rope fast……. entirely carried away.”

Mr Marshall has his seaboots on and oilskins, also Mr Ducat has his seaboots on. He had no oilskin, only an old waterproof coat, and that is away. Donald McArthur has his wearing coat left behind him which shows, as far as I know, that he went out in shirt sleeves.

Next time, I will show you the conclusions of the NLB Superintendent who also visited the island. He, like Joseph Moore, was well aware that the box constructed to keep all the ropes and other equipment safe was 110 feet above the sea.