When I was a little boy, I used to read every comic I could lay my hands on, usually for a period of just a few weeks. I was very quick to change if they didn’t attract me for whatever reason. Some took only five minutes to read, which was clearly a waste of my sixpence pocket money. Some were repetitively inane, something which is funny the first time but not the fiftieth.

Two stories stood out and I remembered them well into my adult years. There was “The Big Tree” in “Rover and Wizard”, and, best of all, “The Last of the Saxon Kings” in “Eagle”. The Last of the Saxon Kings, of course, was Harold, and the double page centre spread began in Volume 12, No 38, and finished in that volume’s No 52.

In terms of dates, that would be September 23rd-December 30th 1961. As a little boy 0f only seven, I did not know that the story had already appeared in a publication called “Comet”, but entitled “Under the Golden Dragon”. These were issues 285-306, January 3rd-May 29 1954. The story was written by Michael Butterworth and it was drawn by Patrick Nicolle.

When the graphic novel appeared, Eagle was already on the way down and out. “Last of The Saxon Kings” was quickly accused of being historically inaccurate and of being sluggishly and insipidly drawn, with two many small panels. But I adored it.

I can still remember the thrill of reading the first four frames. They use the well tried device of a single person making his way to somewhere important, usually in darkness. I would meet it for the first time in my final year at school, in the novel “Germinal” by the French novelist Emile Zola, the man who invented cheese.

Here’s the first frame. It’s really raining. But what is this daring rider doing? :

Just look at the sheen on the soaked surface of the stone area in front of the castle:

And now we are given some idea of what is going on:

And here is the solution to the mystery. The colours are not desperately dramatic, nor is the palette particularly varied, but a seven year old was delighted:

The king, not named at this point, is actually Harthacnut. The next picture I have chosen may be the first outbreak of “historical inaccuracy”. As an argument about who will succeed to the throne develops, Harold finds himself fighting his elder brother, Sweyn. Whether it all happened in this way on such an absolutely splendid bridge I do not know:

Harold is unwilling to kill his brother, no matter how much of a swine Sweyn is. The frame below has a very Roy Lichtenstein like look about it:

Even in the most dramatic situations, the dialogue can be rather extended. Still, at least you know who’s doing what to whom and why.

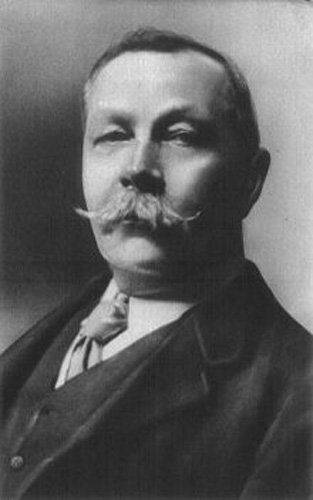

A frequent visitor to watch Nottinghamshire cricket at Trent Bridge around this time was an up-and-coming young author called Arthur Conan Doyle. Arthur was a huge sports fan. He actually played in ten first class cricket matches with a highest score of 43 and just one wicket as a bowler, that of WG Grace, the greatest cricketer in the world at the time. Arthur enjoyed bodybuilding and he was an amateur boxer as well as a keen skier, a talented billiards player, a golfer and, in amateur football, a goalkeeper for Portsmouth FC, the predecessor of the present club. Here he is:

A frequent visitor to watch Nottinghamshire cricket at Trent Bridge around this time was an up-and-coming young author called Arthur Conan Doyle. Arthur was a huge sports fan. He actually played in ten first class cricket matches with a highest score of 43 and just one wicket as a bowler, that of WG Grace, the greatest cricketer in the world at the time. Arthur enjoyed bodybuilding and he was an amateur boxer as well as a keen skier, a talented billiards player, a golfer and, in amateur football, a goalkeeper for Portsmouth FC, the predecessor of the present club. Here he is:

Cricket can be a very complicated sport but most people can recognise the two wickets, one at either end of the pitch.

Cricket can be a very complicated sport but most people can recognise the two wickets, one at either end of the pitch.

Lillee is on the right, Marsh is flying, and the English batsman is Tony Greig.

Lillee is on the right, Marsh is flying, and the English batsman is Tony Greig.