While I was doing the researches for these sad and grim tales of Bomber Command, I came across a number of interesting details which I would like to share. Perhaps one or two loose ends might be tied up.

The first is only loosely connected with the collision of the two unfortunate Lancasters returning from Leipzig on February 20th 1944. I noticed that one of the casualties, Flying Officer Ronald Harry Fuller, was buried in Cambridge City Cemetery. Given that Cambridge is not particularly close to Marylebone in London, where Ronald lived, I decided to look up the details of this cemetery on the Internet. I was genuinely shocked by what I found about the war casualties there. Their names and most basic of details occupy fully an unbelievable 68 pages on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website. Just enter the words “Cambridge City Cemetery” in the line marked “Cemetery or memorial” and press “Search”:

The very last page is grimly ironic. It lists four Australians, all of them obviously interred a long, long way from home.

One is from the Great War, George Ernest Young of Camberwell, Victoria, Australia. He was aged 28 and died only 12 days from the end of the conflict. The other three interments are all Second World War flyers:

Flight Sergeant George Louis Yensen was a Mid Upper Gunner aged just 20. He was killed on August 31st 1943 in a Short Stirling I of No. 1651 Heavy Conversion Unit of Bomber Command, Serial Number N6005,Squadron Letters probably F-D2. Here is a flight of three Stirlings:

The name of George’s unit means he must have perished well before his training for heavy bombers was even complete. George died along with eight other young trainees on board this aircraft. Two of them were from the Republic of Ireland. Apparently the plane took off from Downham Market near Cambridge at 9.30 pm. presumably just as the daylight was beginning to fade. Suddenly, ten minutes after takeoff, for no apparent reason, the aircraft banked steeply and then spun into the ground just a mile or so north of Shippea Hill on the Cambridgeshire-Suffolk border, and around seven miles from Ely. The orange arrow marks the crash site:

The next Australian, Alan Geoffry (sic) Young was 21 years old when he was killed. A member of the RAAF’s 460 Squadron, he was returning from a bombing raid on Stuttgart. His Lancaster was caught in a blizzard and crashed some ten miles south of Grantham at North Witham. All seven members of the crew were killed. By coincidence, young Alan perished on February 21st 1944, the very next day after the Leipzig raid which inspired the first of these articles:

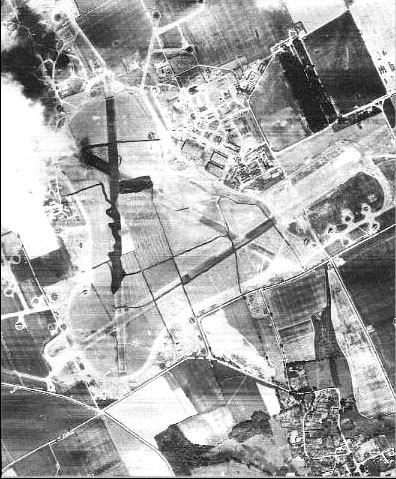

Flight Sergeant Ian Bailey Yorkston was killed in an accident on March 4th 1945, flying in a Lancaster I, Serial Number PD431,Squadron Letters H4-V. Ian was in No. 1653 Heavy Conversion Unit RAF, and he was just 25 years of age. His parents were Christian missionaries and had worked in China where Ian grew up. Seven other young men perished in the crash. The plane had taken off from North Luffenham for a cross-country training flight at 11.30 in the morning, and returned to base at 4.00 pm. As the aircraft landed, it bounced quite severely. The pilot increased the power and prepared to go round for a second landing attempt. As it climbed away, the aircraft’s undercarriage hit an obstruction and then ploughed into the tops of several trees. It finally crashed near the village of Edith Weston, just four miles south east of Oakham in Rutland. The orange arrow marks the crash site:

This was not Ian Yorkston’s first crash. On August 18th 1944, with “D” Flight of No. 1651 Heavy Conversion Unit he was flying in a Short Stirling III, Serial Number LK519, Squadron Letters QQ-O. Taking off on a night exercise from Wratting Common at three minutes to ten the previous evening, the crew were returning at six minutes past two. They requested, and were given, permission to land, but then there were problems with the Stirling’s immensely lofty and complicated undercarriage:

For forty minutes, a tense dialogue took place between the aircraft and Flying Control. At three minutes to three, a garbled message came from the aircraft which was heard to contain the phrase “crash land”. The Stirling came in at tree top level, flying towards No 4 runway which already had a second Stirling parked on it, having suffered a burst tyre. In the resulting collision, the Trainee Pilot, Flight Sergeant Alan Woodbridge (aged 23) was killed. He was buried in his native village Up Nately, in Hampshire. Alan had himself already been in an accident on July 26th when a slightly misjudged landing resulted in part of the Stirling’s undercarriage being ripped off. Three weeks later, as we have seen, he was dead.

Ian Yorkston’s brother, Flying Officer Gordon Cameron Yorkston, was also killed, not in training though, but in combat with No. 251 Squadron. He was only 21 years of age when he perished on March 17th 1945, in the icy waters off Iceland. The squadron was tasked with carrying out Air Sea Rescue and Meteorological Flights out of Reykjavik This was only 13 days after his elder brother, Ian, had been killed. Gordon’s remains were never found and his sacrifice is commemorated on the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede near Egham in Surrey. This memorial is dedicated to RAF personnel who died in World War II and who have no known grave anywhere in the world. Many were lost without trace. There are an amazing 20, 310 names on the memorial:

I actually found a website which listed all of the brothers who had died in service with the RAAF in World War Two. There were at least fifty pairs and included three Sandilands, three Eddisons and four brothers called Bernard. What a sacrifice to be asked to make!

The second final, grim, point concerns the unfortunate collision witnessed by Driver Marie Harris. This took place on December 16th 1943, as the two aircraft took off to bomb Berlin.

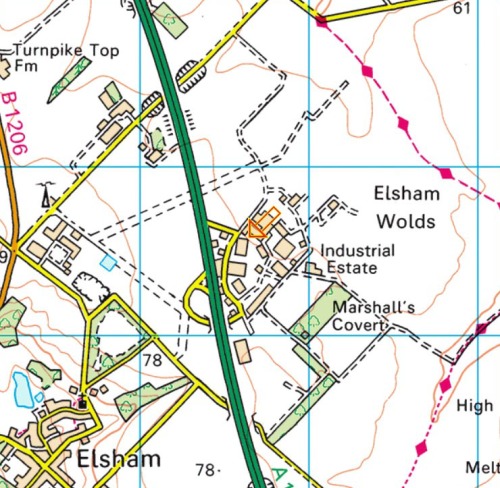

What I found really quite shocking was that there is another memorial very close by in what is actually only a very small area of Lincolnshire. It pays tribute to yet another crashed Lancaster, a plane from No 12 Squadron at RAF Wickenby, which was shot down by a German night intruder just before half past midnight in the early hours of March 4th 1945.

This was Lancaster PB476, Squadron letters PH-Y, and the brave young men remembered were the Flying Officer Nicholas Ansdell (Pilot, 21 years old, from Churt in Surrey), Flying Officer Alexander Hunter (Navigator, age 33, from Dunfermline, Scotland), Flying Officer Freddie Heath (Bombaimer, aged 22, from New Malden, Surrey), Sergeant Ronald Schafer, (Flight Engineer, aged 23 of Earley in Berkshire), Sergeant Robert Parry, (Wireless Operator, aged only 19 from Dagenham, Essex), Sergeant Arthur Walker, (Mid – Upper Gunner, aged only 20, of Risley, Derbyshire) and Sergeant William Mellor (Rear Gunner, aged just 19,from Hatherton, a hamlet in Cheshire.)

Here is the lane next to the field where the aircraft crashed and the monument on the left:

They were victims of a German night fighter initiative called “Unternehmen Gisela” or “Operation Gisela”

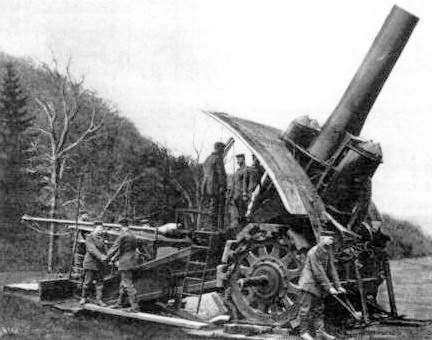

This involved large numbers of twin engined German night fighters, armed with Lichtenstein radar:

The aircraft left the Continent and flew across the North Sea to England in an effort to destroy as many of the vulnerable bombers as possible as they arrived back from Berlin:

The fighters flew at low level, under a storm front and in heavy rain, to remain under the British radar defences. They were then able to attack over a wide area, looking for RAF navigation lights and then flying underneath the bomber to make use of their upward pointing Schräge Musik twin cannons. In this case, the cannon are just behind the cockpit, clearly offset for some reason:

Around 25 Lancasters or other bombers were either destroyed or severely damaged in this operation. A total of 78 aircrew were killed and 17 civilians perished. The Germans lost 45 airmen.

One final word. All of the websites I have used can be reached through the links above. I could not have produced this article, however, without recourse to the superb books by W.R.Chorley. Their detail is almost unbelievable and I would urge anyone interested by the bomber war to think seriously of purchasing at least one of them. The books bring home just how many young men were killed in Bomber Command during the Second World War. When the first book arrived, my daughter thought it contained all the casualties for the whole war, but, alas, it was just 1944.