In a previous article, I wrote of how I had visited the RAF airbase where my Dad, Fred, had served during the Second World War, RAF Elsham Wolds in north Lincolnshire. Look for the orange arrow:

Not much of the original airfield was left, just a single aircraft hangar, which looked like a very large Nissen hut and was now painted white.

Very little else remained of 103 Squadron’s old home, beyond various stretches of derelict runway, now mostly covered in huge piles of builder’s rubble. Half of one runway has Severn Trent Water Authority buildings standing on it. The other end has a metal fence built over it. A second runway has a major road, the A15, constructed more or less right on top of it:

If you knew where to look, and could recognise what they were, there were still quite a number of disused dispersal points. Overall, it seemed a very long time indeed since those dark painted bombers had taken off, every single one of them straining their Merlin engines for altitude as they passed low over the village of Elsham. Within just a few miles of Elsham is Reed’s Island, a distinctively shaped land mass, situated in the estuary of the River Humber. Look for the orange arrow. When they were flying back to base, like all the other members of the squadron, the pilot of Fred’s aircraft used it as a rough and ready aid to navigation. Note Elsham village in the bottom right of the map:

Fifty years later, I myself was to visit Reed’s Island, not as a wireless operator / air gunner, but as a birdwatcher / twitcher, to see a rare Kentish Plover, which was spending the winter there:

In Fred’s time, the man in charge of Bomber Command was Arthur Harris:

According to Fred, Harris, who was usually known to his men not so much as “Bomber”, but rather as “Butcher” or “Butch” Harris, was an absolute tartar. Whenever he came across a bomber which was not in service, he wanted to know why it was still being repaired, why it was not yet back in action, and when would it be possible for it to return to dropping bombs on the Germans.

Despite much encouragement from members of his own staff, Harris did not often visit airbases, because he felt that all the painting and decorating which would be carried out for his arrival was something which would inevitably interrupt the much more important business of killing the enemy.

Fred always used to say that he had actually seen Harris, though, and my subsequent researches have revealed that the great man did in actual fact visit Elsham Wolds, on September 16th 1943 to speak to 103 Squadron. He was greeted with sustained cheering by everyone present, and I presume that this must have been the occasion when Fred saw him.

And sure enough, Harris spent much of his time at Elsham Wolds trying to find out why aircraft were being repaired, how long the work would take, and exactly when they would be back on strength, ready to drop bombs on the Germans.

In actual fact, Fred had been very lucky to have seen Harris. Despite those constant urgings by his fellow officers, he was only ever to make around six visits to Bomber Command airbases during the whole time that he was the head of that formidable organisation.

Fred never mentioned to me any of the men he met during his time at operational bomber airfields, although I do remember that he once mentioned the presence of a Jamaican pilot with 103 Squadron at Elsham Wolds, presumably because this man was black, which would have been unusual in Bomber Command at the time.

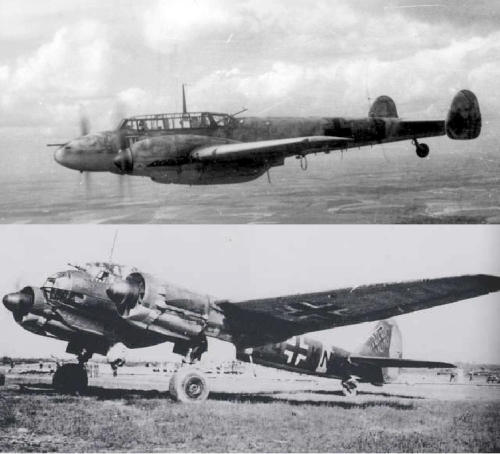

Years later, totally by coincidence, I was surprised to see in “Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War”, that on February 15th 1944, a Lancaster Mk III, ND 363, with the squadron letters PM-A of 103 Squadron, took off from Elsham at 17.10 to bomb Berlin. The plane was shot down by a night fighter two minutes before eleven o’clock, crashing into the sea near the island of Texel in Holland. The entire crew was killed. Among them was Squadron Leader Harold Lester Lindo who, although he was in the Royal Canadian Air Force, was actually from Sligoville in Jamaica. Lindo was not, however, a pilot but a navigator. Another Caribbean navigator was Cy Grant, who came from British Guiana and arrived in England to join the RAF in 1941. After undergoing initial training, he too was posted in 1943, to 103 Squadron at Elsham Wolds, as one of the seven-man crew of an Avro Lancaster bomber. Here he is:

I have mentioned before the risks of bombing Germany, statistically four times more dangerous than attacking anywhere else in the rest of occupied Europe. In 1943, for example, in some squadrons, losses in the Battle of Berlin sometimes ran as high as twenty per cent. At Elsham Wolds, 103 Squadron had the lowest losses in 1 Group but they still lost 31 Lancasters in the Battle of Berlin, with, perhaps, 217 men killed. At the time, Bomber Command pilots, of course, received the princely sum of £5 per week for their efforts, with other members of the crew paid correspondingly less.

During his time at Elsham Wolds, Fred conceivably came across the record holding Lancaster in Bomber Command, although I do know that he never flew in it on an operation. ED888 was to carry out an unprecedented 140 bombing raids over enemy territory:

This legendary Lancaster began its operational career on the night of May 4th 1943, initially in B Flight of 103 squadron, where she was known as “M-Mother”. In November 1943, to mark its fiftieth operation, the aircraft was awarded her very own Distinguished Flying Cross. When she then passed into Elsham’s second squadron, 576 squadron, she became known as “Mike Squared”. To commemorate her completion of one hundred sorties, the aircraft duly received a Distinguished Service Order. By now she had returned to 103 squadron and was known unofficially as “M-Mother-of-them-all”. Eventually to complete 140 operations with two Luftwaffe fighters shot down, ED888 finally received a Bar to her Distinguished Flying Cross:

The aircraft was struck off charge on January 8, 1947 and scrapped without the slightest thought of preservation in a museum. Yet she was the greatest Lancaster of them all.

The only part of “M-Mother” which remains nowadays is, in fact, her bomb release cable, which was taken off the aircraft in 1947 by Flight Lieutenant John Henry, one of three Australian brothers, who were all in 103 squadron and who did, on one particular operation, all fly together to bomb Cologne. Flight Lieutenant Henry flew “M-Mother” on its very last trip down to the Maintenance Unit at RAF Tollerton in Nottinghamshire, where it was finally broken up:

Not everything was hearts and flowers in Bomber Command though. My Dad once had a trick played on him by men who perhaps should have known better, but who could be forgiven a lot for finding any way whatsoever of dealing with some appalling events.

One day, on an unknown airfield in an unknown year, probably towards the beginning of his air force career and possibly at Elsham Wolds, the young Fred was approached by one of his superiors, perhaps a Flight Sergeant. Fred was told that he had to come and help get the Squadron Leader back from the runway. He innocently thought that it would merely be a matter of going out and telling the man, politely, that he was now needed to come inside. Fred did wonder, however, about the strange objects they were carrying out there onto the vast expanse of tarmac:

Fred could not see anybody at all as he stepped out onto the runway. They walked further and further. Suddenly Fred realised why they were equipped with a sack and a shovel. The Squadron Leader was out on the runway, but was, unfortunately, no longer a living, recognisable, human being.

The poor man had been the victim of a crash as he came in to land, and was now just a collection of smears of what Fred described to me years later as “lumps of hairy strawberry jam”. He was picked up with the shovel, put into the sack, and then the two young men went back to their own lives.

As I found out in later life from various books I had read, this term, “strawberry jam”, was frequently used by members of Bomber Command to refer to the residue remaining after what might nowadays be termed “catastrophic and large scale injuries to personnel”.

The phrase typifies the kind of outcome one can expect when the human body is placed in a heavy metal machine travelling at hundreds of miles an hour, and there are then sudden and calamitous problems:

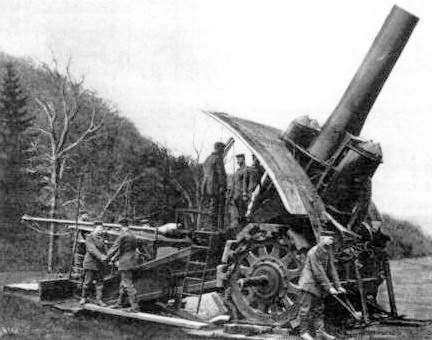

Perhaps Fred himself was familiar from his own father, Will, with the Great War equivalent of this Second World War expression. The Great War was fought with big guns, huge artillery pieces, and most men were killed when a shell landed and blew them to smithereens, “knocked to spots” as the soldiers of the day grimly called it:

It has been suggested elsewhere, of course, that this use of slang to describe being killed, in what were frequently the most horrendous of fashions, was a sub-conscious means of reducing the natural fears of these brave young men of Bomber Command. If, therefore, you “got the chop”, “went for a beer”, “went for a burton”, “your number came up”, “you met the Reaper”, or as the Americans in the Eighth Air Force used to say, “bought a farm”, the expressions became events no more sinister than the other famous slang expressions of the RAF, such as Wizzo” or “Wizard”, “Crackerjack”, “ops” “kites”, “props”, “sprogs” and the one which has come down all those years to our own time, “Gremlins”.