There is no shortage of theories as to the identity of the murderous beast I described recently, la Bèstia de Gévaudan,which terrorised a whole province of France from 1764-1767, and claimed upwards of a hundred victims, mostly women and young girls. From what I have read, but above all, from what I have watched on “Youtube”, basically, you will have to make your own choice.

The creature was, therefore, perhaps a single enormous wolf, or maybe a number of wolves in a single pack, or even a large number of wolves in a number of separate packs.

Less fancifully, it could have been some type of enormous domestic dog, or perhaps even a wolf dog hybrid, perhaps with a red coloured mastiff involved. Its supposed invulnerability to bullets was because it wore the armoured hide of young boar.

It may have been a hyena although this species is thought to have been long extinct in Europe at this time. It has even been suggested that it was not a real animal, but a sex-crazed serial killer who dressed in a fur costume, pretending to be a wolf. In the same vein, it was perhaps a werewolf with a penchant for hunting women and young girls.

An initial, perhaps simplistic approach, is quite simply to look at pictures of the beast, and to compare it with photographs of the most likely candidates, and then to make up your own mind.

Firstly, here are some pictures of the beast itself. You need to bear in mind that they are unlikely to have been drawn directly from a witness descriptions, and that many of them may have been mere copies of the work of other artists. Furthermore, at this time, it was accepted practice to draw animals in a very stylised fashion, rather than in the more accurate zoological one. Because of this, therefore, the head and limbs are often out of proportion, and the body is frequently too large for a small head and legs. In many pictures, the artist sought to portray an unknown animal by reaching into his knowledge of Heraldry…

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Here are some photographs of wolves. I have deliberately picked what I consider to be the largest individuals, and to provide illustrations of animals in poses which are hopefully similar to those in the engravings of the beast.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Here are some photographs of what are usually called wolf dog hybrids. Having looked at a much larger number of them on the Internet, I do feel that most can be dismissed immediately because an ordinary person would think that they were pure bred wolves. They are only noticeably different when crossed with a very distinctive breed of dog.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Many cryptozoologists favour the hyena. Certainly, a number of the original drawings from the eighteenth century are titled as being “la Bèstia de Gévaudan, the hyena”. Many of them, even the most wolf-like, have their flanks covered with either stripes or spots.

This picture was allegedly drawn by the killer of the second beast, Jean Chastel.

Here are some pictures of the striped hyena.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

And here are some pictures of the spotted hyena.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Basically, you pay your euros, and you take your choice.

As blogposts cannot be of infinite length, let me summarise the fors and againsts of all the possibilities as I see them.

A wolf or wolves?

This is the mot acceptable of a very large number of explanations. Certainly, the prints found were deemed to be those of a wolf. Monsieur Antoine de Beauterne who was to kill the first animal, the Wolf of Chazes, said that there was « aucune différence avec le pied d’un grand loup » “no difference with the pawprint of a large wolf”

BUT…

Wolves do not normally attack Man. The locals used to kill around 700 wolves every year, so they all knew what a wolf looked like and could defend themselves against them. All the witnesses were adamant that the animal was not a wolf, but an animal that they did not know. That is why it was immediately christened “la bèstia”. Neither can wolves have a white breast and underparts, as a large number of witnesses said in their descriptions and, indeed, as is portrayed in many of the contemporary illustrations. Only a hybrid animal could exhibit this pattern of coloration.

Wolves do not strip the clothes off their victims, neither do they decapitate their prey.

After the Wolf of Chazes was killed, the deaths did not stop.

A rabid wolf?

An animal diseased in this way would not have been afraid of Man, but it would certainly have died well before the three year period was up. A number of rabid wolves? Isn’t that possibly stretching the argument a little?

A hyena?

The animal would certainly have been unknown to the inhabitants of the area. Members of the French nobility, however, frequently indulged themselves by importing exotic animals such as lions and tigers into the country, and we know that hyenas were brought into France at this time. So too, hyenas are supposedly relatively easy to train, or at least, easier than you might expect! Whether this would extend to converting them into fearless and ferocious attack animals is a different matter, however.

Hyenas are certainly capable of decapitating their prey. I have been unable to ascertain if they take the clothes off their victims, although I would have thought that they might have needed opposable thumbs for any particularly intricate garments.

BUT…

the second beast to be killed, the Bête de Chastel, did not have enough teeth to be a hyena. This creature was, without doubt, a canid of some description, according to the King’s Notary, Roch Étienne Marin, the man who carried out what appears to be an extraordinarily thorough autopsy. On the other hand, the creature was also examined by the famous Comte de Buffon, an extremely famous scientist and naturalist of the day, whose ideas were to have a great influence on Charles Darwin. Buffon pronounced it to be a very large wolf.

The Striped Hyena, which resembles most closely perhaps, la Bèstia, does not hunt but scavenges. The Spotted Hyena does hunt for itself, but nobody has ever really mentioned spots as a feature of la Bèstia.

In one of his blogposts, C.R. Rookwood suggests another exotic solution. He suggests that la Bèstia was a mesonychid, a prehistoric mammal related to present day whales. They were very large predators with huge heads, long tails, and hooves instead of feet. The largest was Andrewsarchus mongoliensis, known only from its skull, minus the jawbone: for this reason, illustrations of its colour are, for the most part, just well informed guesswork. The structure of the animal is based on the other members of the family, whose skeletal structure is better known.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

This animal does fit quite closely the description given by many of the peasants who saw la Bèstia. A few of the reports did mention hooves instead of feet, although the creature may well have been described as having hooves to emphasise its connection with the Devil.

BUT…

How could a gigantic, fierce, flesh eating mammal have survived from a prehistoric era until the eighteenth century, without anybody noticing it?

A human serial killer?

Humans can remove dead people’s clothes. Humans can decapitate their victims. Some bizarre serial killers would enjoy the chance to mask their activities behind the depredations of a very large trained carnivore.

BUT…

All the reports by eye witnesses say that only an animal was involved. This idea of a human serial killer can only be maintained if mutilated bodies were found and there were no eye witnesses who saw an animal attacking them. Only in the Cantal area, apparently, were these circumstances fulfilled.

Of late, many people have become increasingly concerned by the involvement of Jean Chastel in this marvellous enigma. Jean, a farmer and inn-keeper in the province of Gévaudan, and his son Jean-Antoine, have come under suspicion because when both of them were imprisoned for a period because of their aggressive attitude to two of Francois Antoine’s gamekeepers, the number of attacks by the monster diminished noticeably.

It has therefore been put forward that la Bèstia was the result of Jean’s crossing either his own or his son’s red-coloured mastiff with a wolf, and then subsequently training it to kill. Almost all the evidence is perforce circumstantial, but much of it is quite compelling.

The creature may have been, therefore, a particularly aggressive hybrid, which Jean-Antoine Chastel trained to have no fear of human beings, but instead to attack and to kill them. Witnesses have said that if its attacks were met with strong resistance, la Bèstia would retreat fifty yards or so, then sit and wait, as if sizing up the situation, before finally returning to the fray. This has been taken to be the behaviour of a trained animal, unafraid of its opponent, rather than a wild one, whose natural instinct in an equal contest would have been to save itself by fleeing. Furthermore, witnesses thought that la Bèstia was driven not by hunger but by its own fury and an innate aggressiveness. It could also be more agile and jump much higher than a normal dog.

According to hunters in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, crosses between dogs and wolves were invariably very varied in appearance with dark or light tinges, sometimes marked with yellow or white or striped a little like a zebra. This, of course, agrees with many of the eye witness descriptions of la Bèstia.

Here are some pictures of mastiffs, although it is very difficult to know exactly what they looked like two and a half centuries ago. Nowadays, they simply don’t look particularly fierce….

Here is an English Mastiff around 1700.

If we are going down the road of wolf-dog hybrids, then I was quite attracted to a long extinct breed of German bulldog, or Bullenbeisser…

On the other hand, others have said that no successful interbreeding of a Mastiff, or Mastiff type dog, has ever been successfully carried out with a wolf, even though such a hybrid might explain the colours noted by many witnesses.

From the summer 1764 to its death in 1767, la Bèstia wandered over vast distances in almost no time whatsoever. Perhaps the two Chastel were conveying their creature around the province by some artificial means…an explanation of the high frequency of attacks spread over a not inconsiderable area.

On many occasions, people reported the apparent invulnerability of the creature when either stabbed or shot at. It has been suggested that it was wearing some kind of body armour made from the skin of a wild boar. Many witnesses told of the creature being shot several times by experienced hunters, and not being affected by it. Other witnesses spoke of its entrails hanging down after it was stabbed. Could this have been the strapping for some kind of home made armour?

When it was killed, la Bèstia died in the parish of La Besseyre Saint Mary, where Jean Chastel and his son lived. Perhaps they felt that they were about to be discovered, so they shot the creature and then manufactured a tale of heroism and religious devotion to snatch a glorious propaganda victory from the jaws of ignominious discovery and defeat.

As to why the two Chastel would want to kill so many of the people in the area where they lived, that remains a matter of pure guesswork. Certainly, Jean Chastel was supposed to have been an unpopular loner, and given his previous record of various episodes of fairly serious criminal behaviour, he may well have been a man who the locals disliked and feared in equal measure.

Perhaps les Chastel, père et fils were rejected and hated by local women and children, and then took their massive revenge on them, like those American teenagers who return to their High School and kill everybody they can. Perhaps they were sexual psychopaths who enjoyed killing and eating women and little girls.

One further detail which may be of significance is that the loud, belligerent and generally anti-social behaviour of the father, Jean Chastel, seems to have changed profoundly from May 16th 1767 onwards. On this date, in the village of Septols, Marie Denty was attacked in a little lane near her house, right under the eyes of her parents, and killed, just before her twelfth birthday. Supposedly, she and Jean Chastel were very close friends and he doted on her like the grand-daughter he never had. Now he was “fou de douleur”, “mad with grief”, and seemed about to lose his sanity. Perhaps, les Chastel and their appalling pet had killed by mistake. Certainly, his ne’er-do-well son, Antoine, seemed suddenly to be released from an evil spell, and he turned straightway to God. Jean spent his time in pure pursuits such as prayer, confession and penitence. For his redemption to be complete, he and he alone had to be the man who finally killed la Bèstia. According to which sources you believe, in best werewolf killer tradition, he made some silver bullets. Or perhaps, he made them from molten lead which had had a statue of the Virgin Mary dipped into it. Or perhaps he made them from the medals of the Virgin Mary which he wore on his hat. Whatever the case, he certainly had them blessed at a religious ceremony.

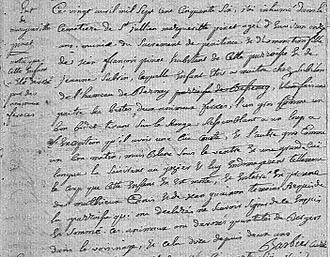

The manner in which he killed the creature is extremely suspicious, and could very easily be interpreted as a tale told merely to satisfy contemporary religious feelings, and to exonerate a man who is not bravely hunting down a ferocious killer beast, but who is, instead, shooting it through the head in its kennel before the locals find out it is actually his beloved pet, and then string him up from the nearest tree. The following account I have translated from the French Wikipédia

“On June 19th, the Marquis d’Apcher decides to organise a beat around Mont Mouchet in the wood of la Ténazeire. He is accompanied by a few neighbours as volunteers including Jean Chastel reputed to be an excellent hunter. The latter finds himself at a place called la Sogne d’Auvers, a crossroads where he sees the animal go past. Chastel fires at it, and manages to wound on the shoulder. Quickly the marquis’ dogs arrive to finish off the beast.”

“As regards this rifle shot, Legend has preserved the romanticised words of the priest Pierre Pourcher which he used to say came from tale told by his family, “When the beast came along, Chastel was saying prayers to the Holy Virgin. He recognised it straightaway, but through a feeling of piety and confidence in the Mother of God, he wanted to finish his prayers. Afterwards, he closes his prayerbook, folds his glasses up, puts them in his pocket and takes his rifle. In an instant he kills the beast which had been waiting for him.”

“A week after the destruction of the beast by Jean Chastel,on June 25th, a female wolf which according to several witness accounts used to accompany the beast itself was killed by Sir Jean Terrisse, one of the hunters His Grace de la Tour d’Auvergne. He received £78 as a reward.”

Perhaps they were acting on behalf of somebody else. The usual favourite is Jean-François-Charles de La Molette, the Count of Morangiès. He may have wanted to destabilise the area, so that he could take over when the revolution inevitably came. There were others. The Church wanted to teach the King and the members of the intelligentsia of the time that free thinking is frowned uon by God….

“Return to the Ways of the Lord or face the Hound of Hell”

As I said before, basically, you pay your euros, and you take your choice.

I had just finished my investigations about la Bèstia de Gévaudan, and had made up my own mind that all the devastation could be attributed, without necessarily knowing the real motivation behind it, to Jean Chastel and his son Antoine.

And then I bought “Real Wolfmen: True Encounters in Modern America” by Linda S. Godfrey. I was enjoying reading this interesting and innovative book, when I stumbled upon page 93 which was about the Wampus Cat of Ariton in Alabama.

“The man who wrote me was disturbed by unidentifiable animal sounds while camping on his ten acres on the Pea River near Ariton, which lies about half an hour’s drive south of the picturesquely named town of Smut Eye. His normally rambunctious standard poodle refused to leave the safety of his trailer that afternoon, and the man was having a cup of tea at about 5.00 p.m. when he heard loud rustling sounds coming from outside the camper.”

“As he peered out the camper window he noticed a large black furred animal with a doglike face surveying his campsite on all fours. It was bigger than his standard poodle and, he said, “Looks like a cross between an ugly collie and an even uglier lab.” Weirdly, it sported a white chest.”

“The creature ambled nonchalantly through the camp and when it jumped over a fallen tree, the man saw that it had a long, sinuous tail like that of a cougar. He reported the creature to the area game warden who said that while she didn’t know what it was, others have reported seeing it, too!”

You can pursue this interesting hunt for truth a lot further if you have any knowledge of French. There are three exceptionally good videos about la Bèstia which can be found on a tourist website for the Auvergne region. They are well worth your time, and seem to portray this most baffling of stories in a fairly reasonable and sensible way. Un, deux et trois.

If you want to see even more videos about la Bèstia, then go to this website which is the French equivalent of “Youtube”. If you search for “la Bête du Gévaudan”, you will find a huge number of films, varying from 15 or 20 seconds long to an hour or more. On the first page, there are eighteen different videos, a further eighteen on the second page, and any number of pages after that.

Bonne chance! And don’t be put off by having to practice your French!