John Michael Taverner Saunders was born on March 14th 1922. His father, Mr W Saunders was a commercial traveller, and the family lived at Park View in Redhill, a suburb of Arnold to the east of the Mansfield Road:

John was one of the young men who carved their name and message on the window sill in the High School’s Tower:

John entered the High School on September 18th 1930 as Boy No 5459.

He was only eight years of age.

He passed through a succession of teachers and forms. First Form D with Miss Webb. Here is the best photograph of her I could find:

Then it was First Form B with Miss Baker. And First Form A with Mr Day and the School Nature Study Prize. Then the Second Form A with Mr “Tubby” Hardwick, badly gassed in WW1. Third Form A with Mr Gregg and Upper Fourth Form A with Mr “Beaky” Bridge, a very strange man. Here he is on the left:

Then came the Lower Fifth Form A with Mr “Fishy” Roche and then the Upper Fifth Form Classical with Mr “Uncle Albert” Duddell. Here he is:

Teachers and forms pass by with the years. Firstly the History Sixth Form with Mr Gregg, and then, in his second year, Mr Beeby. And very soon, May 20th-21st 1940, John was looking for German parachutists and carving his name.

John received four different scholarships because his parents sometimes struggled with the fees. He was a Dr.Gow Memorial (Special) Exhibitioner and an Agnes Mellers Scholar and a Foundation Scholar and the taxpayer also awarded him a Nottinghamshire Senior Scholarship.

His prize record included the SE Cairns Memorial Prize, Mr Durose’s Prize for History, the Cusin’s Memorial Prize for History, the Bowman-Hart Prize for Music and a Bronze Medal for Reading. He was a Prefect and in the Junior Training Corps he became the Company Quarter-Master Sergeant and then Company Sergeant Major. In sport, he won his First XV Colours at rugby as:

“an improved player and solid scrimmager. A front row forward who gets through a great deal of hard and useful work in the course of a game.”

Here’s his final record from the School List:

John left the High School in July 1941 and eventually finished up with the Royal Artillery. They, of course, had a very large selection of guns, including these giants, designed to bombard the enemy from long range :

This smaller weapon is an anti-tank gun:

And this is an anti-aircraft gun :

John was involved in fighting through the Netherlands, as the British Army tried to rescue the paratroops who had captured the Arnhem bridge but were now surrounded and cut off . Did he realise that fellow Old Nottinghamian, Tony Lloyd, lay in Kate ter Horst’s house in the town, one of 57 paratroopers given a temporary burial in a mass grave in the house’s garden?

And then John played his part in Operation Plunder, the crossing of the River Rhine at a small town called Wesel, all of it organised behind an impenetrable week long smoke screen. Did John Saunders ever realise that two of his schoolmates would die within just a few miles from him? Arthur Mellows (1931-35) and John Hickman (1934-37)? Here’s what was left of Wesel at the end of World War Two:

John survived the war, but despite my best efforts, I could find no more mention of him until February 12th 2013 when he passed away peacefully in his sleep. On March 1st 2013, he was cremated at Macclesfield Crematorium with all donations in lieu of flowers to be made to SPANA (the Society for the Protection of Animals Abroad). He left behind him three daughters, six grandchildren and one great granddaughter.

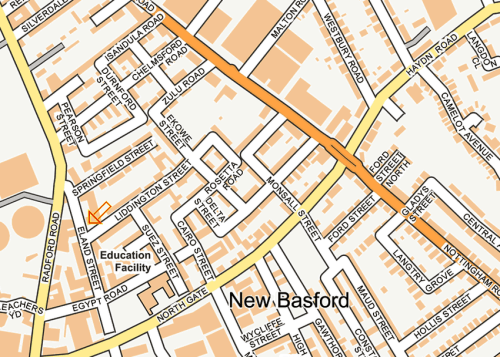

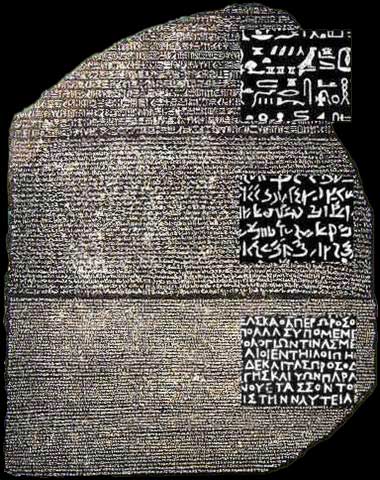

Notice how somebody has put a magnifying glass over each bit, so that you can see the differences. Rosetta Road has no such problems over communication, because 99% of the time, it is deserted, except for cars:

Notice how somebody has put a magnifying glass over each bit, so that you can see the differences. Rosetta Road has no such problems over communication, because 99% of the time, it is deserted, except for cars: