Last time we were looking at how the airliner in which Leslie Howard, the film star, was returning to England, was shot down in the Bay of Biscay by the German Luftwaffe, resulting in the deaths of every single person on board, including the children. Here is some of Leslie Howard’s best work, taken from the now controversial “Gone with the Wind” :

Since that first day of June 1943, there have been literally scores of theories put forward as to why Leslie Howard and the rest of the civilian passengers and crew of the DC-3 “Ibis” were all murdered in this callous fashion. Shot down into the waters of the cold Atlantic Ocean, while travelling to England in an aircraft which was unarmed and the property of a neutral country, namely the Netherlands. And this attack was clearly directed at somebody, because the attackers were eight Junkers Heavy Fighters, armed to the teeth and clearly, sent specifically to destroy this inoffensive DC-3 Dakota.

Leslie Howard’s business manager, Alfred Chenhalls was a fat, bald man who loved to smoke cigars and who occasionally drank alcohol in sensible quantities. It was extremely easy to mistake him for Winston Churchill. What do you think ? Did a German spy see Chenhalls get on the plane and immediatelyt telephone the German Embassy in Lisbon?

Which one is this? Churchill or Chenhalls?

And is this the Prime Minister or a party going bon viveur, who liked nothing better than drinking the very best whisky in large quantities?

“Two bottles for each of us, barman !!! “

As we have seen elsewhere, Leslie Howard was not an English landowning gentleman, but a Hungarian Jew. He supposedly resembled Churchill’s bodyguard, Detective Inspector Walter Thompson. Similarly, Detective Inspector Thompson had the air of an archetypal English gentleman, self assured, self confident, upper class and, most of all, slim. Here’s Leslie Howard:

And here’s Walter Thompson, on the right:

There are other theories, of course.

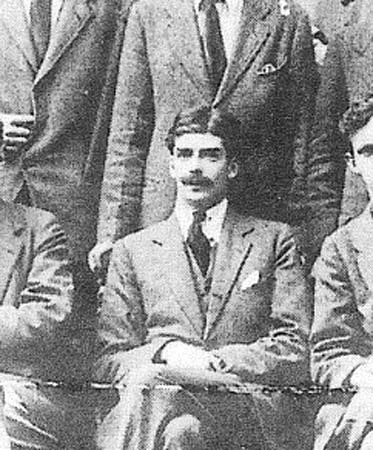

How valid is the theory, though, that Leslie Howard was supposedly the virtual double of Sir Anthony Eden, England’s Foreign Secretary at the time? Here’s Eden at the age of around twenty, as a student at Oxford University……….

There is though, a bit of a giveaway which is tremendously helpful in any “Pick-out-Anthony-Eden” competition. The real Anthony Eden, for his entire adult life, had that stonking great moustache which he fixed into his nostrils at seven o’clock every morning and then didn’t take off until midnight.

And what about the idea, quite widespread at the time apparently, that the Germans thought that Leslie Howard and Reginald Mitchell, designer of the legendary Spitfire, were one and the same man? Leslie Howard we have already seen, and here’s the designer of what began its life as the Supermarine Shrew :

In my mind, the best fit is “Churchill and Thompson v Howard and Chenhalls”. And we must not forget that the only images of Churchill or Leslie Howard seen by most of the attendees of the Dakota’s take-off from London would have been either crudely printed photographs from newspapers or perhaps slightly better quality pictures from magazines. Moving pictures would have been from Howard’s films, or for Churchill , the two minute Pathé News films shown in cinemas during the interval. In other words, confusion was a great deal easier in 1943 than it was in 2023.

It was by no means a completely ridiculous idea, therefore, to suggest that “Churchill–Chenhalls” was on that plane from Lisbon. And for the Germans, it was well worth organising an attempt to shoot down the plane, even if the Prime Minister was supposedly at an important conference in Algiers.

How easy it would have been to alert Berlin, who could then have contacted the fighter base, probably at Mérignac near Bordeaux in southern France, and then telling those eight Junkers Ju88C-6 heavy fighters to take off and intercept the DC-3. Such attacks were in actual fact very rare in the Bay of Biscay, so this particular Luftwaffe operation must surely have been for a specific reason, and for a specific and important target.

And now a whole second level of conspiracy theories swings into action. Perhaps British Intelligence invented the entire story of Churchill’s being on board “Ibis” that day, so that he could fly back home to England in his own private aeroplane, an Avro York. Here’s an excellent short film giving you all the relevant facts about the Avro York, which was basically a different fuselage, set on a pair of Lancaster wings:

There were plenty of people who believed this story that British Intelligence had told the Germans that Churchill was returning to England in the DC-3 that particular day, and that he would be refuelling near Lisbon. In this way, his Avro York would be able to return to London in peace, even if the Dakota finished up in pieces.

And so it goes on, round and round in ever decreasing circles with very little beyond well informed guesswork and random supposition. These are certainly very far from being guaranteed truths.

In 1943, the earliest rumours to surface were that “bon viveur” Alfred Chenhalls had actually been mistaken for Churchill by German agents as he walked out to the plane in Lisbon. Furthermore, this explanation is known to have been the one favoured by Churchill himself. At the same time, though, Churchill was certainly puzzled as to how German intelligence could possibly believe that he, with all the resources of the British Empire’s armed forces and those of the United States at his fingertips, should be reduced to travelling in an unarmed, relatively slow and vulnerable commercial airliner.

The German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, had a very slightly different alphabet, but , again, it was based on names:

The German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, had a very slightly different alphabet, but , again, it was based on names: