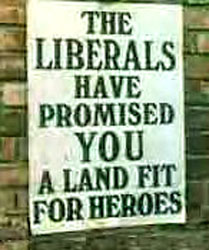

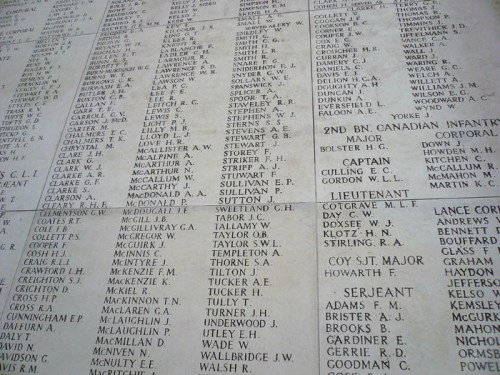

My Grandfather Will, as we have already seen, spent approximately two years four months in a Canadian Army at war. At the end of the conflict, an officer stood at the front of the men on parade, and made a speech about what would happen when they all returned home. With his optimistic words, delivered no doubt in all sincerity by this upper class young man, Will became one of an unknown but enormous number of soldiers who, in 1919, were promised “a home fit for heroes”. Politicians were quick to jump on the bandwagon, of course:

In actual fact, before his return, Will was already very cynical about whether he would receive his just rewards for fighting in the war. Indeed, after just a short time back home in England, he became certain that he was destined never to be given what was due to him. These were the days, of course, when injured ex-soldiers would beg in the streets, unable to find employment. It affected both the victors and the vanquished:

Overall, Will had very little time for high ranking officers. He did not like the way that they refused to visit the front line with its ever present smell of rotting corpses, but preferred instead to stay in the palatial comfort of country houses miles behind the fighting troops:

As a boy, I remember him telling me never ever to buy a poppy for the Haig Fund because he hated Earl Haig so much. He thought that Haig had no regard whatsoever for the casualties among his men, and that he did not care a jot about their eventual, and dismal, fate. Thank God that Will had no access to the Internet and never found out that Haig was Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, KT, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCIE. Will did not realise either that Haig’s wife, Maud, was a maid of honour to Queen Alexandra, wife of King George V, and that that, supposedly, was how he got his job, in charge of the armies of the British Empire. Years before, in 1905, Haig had put his hat in the ring for a plum job at the War Office but his efforts had all been in vain because he was accused of “too blatantly relying on royal influence”. (Groot). Here are Queen Alexandra and her daughters at “Maud’s wedding”:

For Will and a very large number of his fellow soldiers, the establishment of Haig’s post-war charity was merely a means for a guilty butcher to salve his blood soaked conscience:

Instead, Will urged me to give any money I had to the Salvation Army, who had always been on hand, ready and willing to help the ordinary soldier.

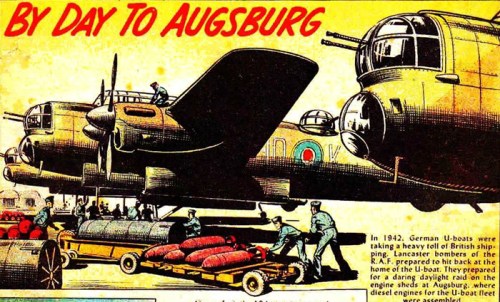

One final tale. In later years, Will told me how, in the Great War, Gurkhas were sent out at night, to make their way over to the German trenches and to kill as many of the enemy as possible. The Gurkhas were paid one shilling for every German’s right ear that they brought back, threading them carefully onto a piece of wire carried on the front of their chest. The problem was, however, that the Gurkhas were extremely efficient and brought back so many ears that the whole process became a very expensive one, so expensive, in actual fact, that it was discontinued. Fierce little chaps. Every time they get their kukris out they must draw blood, even if it is their own:

The senior officers also seem to have considered it vaguely disquieting to kill the enemy in this very direct, but rather brutal, or even unsporting, way.