Last time, I introduced you to Shaka kaSenzangakhona (1787–1828). The Black Napoleon. The greatest military commander in African history. The man who revolutionised warfare on the veldt of Zululand. Shaka, or indeed, Chaka. Either spelling is apparently acceptable.

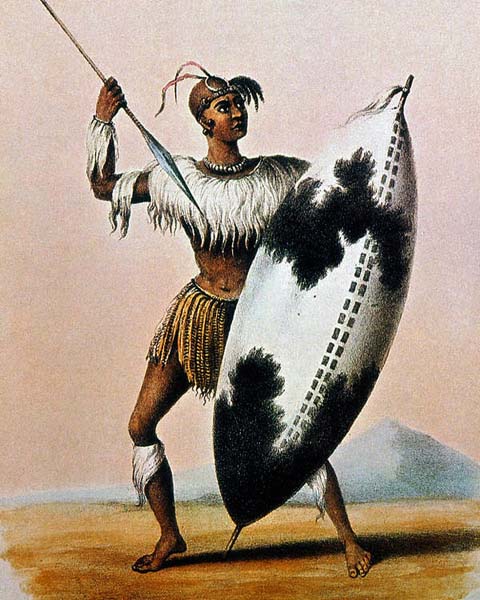

Chaka was no fool. As the Romans had realised two thousand years previously, he soon worked out that the throwing assegai could be thrown straight back at you. He favoured the “iklwa” or ixwa” which he supposedly invented himself. This was “a short stabbing spear with a long, broad, and sword-like, spearhead.” It had a shaft around two feet long, and a blade one foot in length. Here it is:

The longer spear was not abandoned, but it became a one use weapon which the Zulus would throw in unison at an enemy formation before moving in to attack with the iklwa.

Chaka also favoured the use of a particular shield, the “isihlangu”, which means which means “to brush aside”. Here is one from the internet, which dates from 1879:

In an online shop, their reproduction isihlangu shields measure 38″ by 22″, with a wooden shaft of 48″ which protrudes five inches above and below the shield. As I have learnt, most Zulu artifacts are quite variable.

Chaka taught his warriors to use the isihlangu shield in their hand-to-hand attacks. They hooked the left hand side of their shield under the edge of the opponent’s shield, then spun him sideways to leave his rib cage exposed. The “iklwa” was then inserted between the ribs and into the heart for a death blow. In actual fact, the iklwa acquired its name from the sound it made when you pulled it out of the wound it has made.

Chaka also persuaded his men to fight in formation rather than just charging off, like the beginning of a serious disturbance in a pub car park. He taught them the “bull’s horns” formation and they practiced it in times of peace, so that when war came, they were better organised than they had ever been. Here it is:

I borrowed the diagram from this webpage, although I am proud to say that the Zulu phrases were the only things I didn’t know, having been a huge Zulus fan from a very early age. The enemy are the weedy white rectangle at the top of the diagram. The Zulu for “bull’s horns” by the way, is “impondo zankomo”. Anyway, the warriors in No 1, the “isifuba” charge forward like a group of middle aged women in the first minute of a reduced-to-clear designer handbag sale. They engage the enemy, isihlangu shields in action and the sound of the iklwa absolutely deafening. Meanwhile, the horns, No 2, the “izimpondo”, move forward quickly and stealthily and encircle the sides and back of the enemy force. If needed, the reserves, the “umava”, the bull’s loins, No 3, wait in case they are needed. Traditionally, they always faced backwards, away from the battle and looking to the rear, so that they didn’t get over-excited, and then lose their discipline and rush off too soon to join the party. In actual fact, the most frequently occurring time to employ the “umava”, was if the enemy managed to break out of the Zulu encirclement.

All of this manoeuvring could be done because the Zulus had their army divided into regiments. The British in 1879 faced an army of 20,000 men. Their overall commander was Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza with subordinate commanders called Vumindaba kaNthati and Mavumengwana kaNdlela.

The Right Horn was made up of the uDududu and uNokenke regiments, with part of the uNodwengu corps (3,000-4,000 warriors).

The Chest comprised the umCijo, uKhandampevu and uThulwana regiments and part of the uNodwengu corps (7,000-9,000 warriors).

The Left Horn of the bull included the inGobamakhosi, uMbonambi and uVe regiments (5,000-6,000 warriors).

And finally, the Loins, who were the reserves and stood with their backs to the battle were the Undi corps and the uDloko regiment (4,000-5,000 warriors).

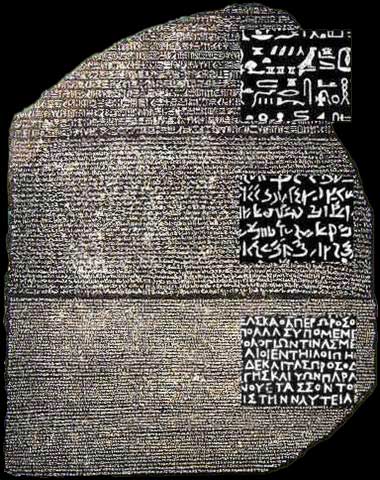

The regiments could be distinguished by the colours of the isihlangu shields, and the different numbers and groupings of the marks on them:

Next time we’ll look at some of the other interesting things that the Zulus got up to.

Notice how somebody has put a magnifying glass over each bit, so that you can see the differences. Rosetta Road has no such problems over communication, because 99% of the time, it is deserted, except for cars:

Notice how somebody has put a magnifying glass over each bit, so that you can see the differences. Rosetta Road has no such problems over communication, because 99% of the time, it is deserted, except for cars: