Last time we had a brief look at The Dramatic Society’s production of Aristophanes’ “The Frogs” in 1924. Just look at those beards. And is one boy in the centre of the back row wearing a white burqa?:

Seven years later, on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, February 23rd, 24th and 25th 1931, the School Play had been “She stoops to conquer”. Here is the cast who contain, perhaps, a few more convincing women than is usually the case. This is because, I suspect, the Dramatic Society were being forced to use many more young boys, not least because the School’s Sixth Form was much, much smaller during the 1930s than it was to become, say, in the 1960s:

Any proceeds from the play, after the deduction of expenses, were used to help finance the Dame Agnes Lads’ Club in Norton Street in Radford.

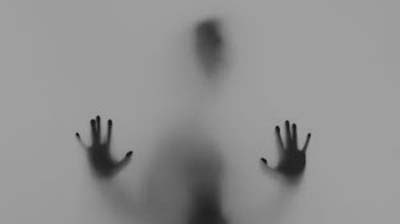

Another popular School Play around this time was “The Rope”. Looking at the photograph below, it seems to have starred Borat and his balding brother. On a more serious note, the young “lady” on the left, within five or six years, will be killed trying to slow down the German advance towards Dunkirk:

This young man, Alfred Warren, was, in actual fact, a most accomplished female impersonator. His first ever role was as Anna Waleska in “Andrew Applejohn’s Adventure”. Witness his review in the School Magazine:

“The School stage has rarely been graced by a more charmingly seductive figure than Anna Waleska. His performance was astonishingly good, especially when one remembers that it was his first appearance. He contrived to give to his impersonation just the right shade of exotic fascination, and if his accent was neither Russian nor Portuguese, it had at least a foreign quality and was sufficiently intriguing. This young man betrayed a knowledge of feminine wiles amazing in one so young, the manipulation of his eyebrows alone being worthy of a Dietrich. One can hardly blame Ambrose for becoming as wax in the hands of such a siren.”

Two years later, in GB Shaw’s “Captain Brassbound’s Conversion”, the School Magazine said:

“The presentation this term was an act more daring than any of its predecessors. There was only one person fitted for the: “prodigious task of portraying so gracious a personage as Lady Cicely. His voice, now at breaking point, just suited her position as mistress of Brassbound’s crew: his seductive manner fitted the beguiler of a dozen men. His part did not allow him this year the opportunity to display those feminine wiles of which, as Anna Waleska, he had shown himself so complete a master, but his expression, now wheedling, now indifferent, was no less successful in enticing the unfortunate victim into her trap. He perhaps tended to overdo that half crouching feline posture which he so often employed against Brassbound. Nevertheless, clad in exquisite garments, which must have cost the society a small fortune, he contrived to overcome the artificialities and discrepancies of Lady Ciceley’s rôle, and for that achievement alone he deserves high praise.”

The young man would not carry forward his talents into the worlds of either stage or screen. He will be killed “somewhere along a canal” near the village of Oostduinkerke, trying to slow down the German advance towards Dunkirk. Not every soldier with the British Expeditionary Force had a free trip back to Blighty: