One more man eating monster to terrorise the local peasants of France was the “Bête de Veyreau”. At a time and in a place both relatively close to the Beast of Gevaudan, his bloodsoaked career peaked from 1799 onwards as he laid waste to an area of France called the “Causse Noir” or “Black Causse”. This beautiful countryside is situated more or less in the south of the Massif Central. Here is the old province of Rouergue, whose capital was Rodez:

And this is a more detailed map, with a red square in the extreme east representing the village of Veyreau. The orange arrow refused to travel abroad:

The province directly to the east of the green area is Gévaudan. The “Causse Noir” or “Black Causse” is dry, rugged and rocky.

There are many mountainous areas and some notable gorges such as the “Gorges de la Jonte”:

Normally, the best approach for these French monsters is to take an average of the various French websites. In this case however, that is not really going to work, because, as far as I can see, more or less every account of this creature is virtually the same, and probably owes a great deal to Wikipedia:

“The Beast of Veyreau was a man eating animal which ravaged an area in the “Causse Noir” not too far from Gevaudan, from 1799 onwards. This was an area where livestock were raised and is nowadays part of the Département of Aveyron. These attacks filled the inhabitants with such immense fear, and the Beast had so many “dozens of victims”, that the locals thought the Beast of Gévaudan had come to their region.”

I have been able to find one person who could expand a little on that:

“around the year 1799, there appeared in the country a beast which filled all the inhabitants with great fear. Its build was slimmer and more willowy than a wolf. Its way of walking had such agility that it was seen first in one place, but then four or five minutes later in a different place perhaps several miles away. And woe betide any child that might meet the creature. The Beast would carry them off and eat them , first the liver and then the limbs. In the space of six months this beast killed three victims including a boy of six whose limbs they found hidden in the earth in the Malbouche Ravine, in the very same place which was, people used to say, the haunt of the ogre.”

Mention of “The Ogre” will lead me neatly to another blogpost in the future, when this long series of familiar crazed creatures, blood soaked beasts, maniacal monsters, feral dogs, wolf-dog hybrids, wolves with attitude or whatever nasty four legged beast you can imagine, becomes just for a few hundred words, a two legged cannibal killer, with the supercool name of Jean Grin.

To get back to the story, this is the tiny village of Veyreau:

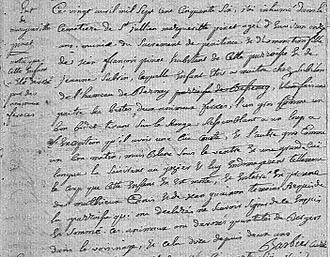

The very best version of the story of the “Bête de Veyreau” comes from a website designed to “découvrir et aimer la Lozère”, in other words to “discover and love La Lozère”, which is one of the most beautiful and picturesque areas of the “Causse Noir”. The account of the Beast below is quoted directly from the parish records of the village of Veyreau, which were collected together in 1870 by the then parish priest, Père Casimir Fages. The road sign below shows that two languages were/are spoken in this southern part of France. “Veirau” is the village name in Occitan. Try the Wikipedia website to read about this ancient language. You will find a really interesting use of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which has been translated into a number of widely spoken languages but then into a good number of others such as Occitan, Gascon, Provençal and half a dozen others. At the very least, it has a wonderful moving map which you can click to enlarge:

As was so often the case in old France, the parish priest was the only literate person in the immediate area, and it was for him to record the history of tiny villages such as Veyreau. Père Fages’ church is still there:

The hard work for this website has all been done by an extremely dedicated gentleman, Monsieur Bernard Soulier. Bernard is the President of the Association “In the country of the Beast of Gévaudan”, in French, “Au pays de la Bête du Gévaudan”. This organisation is based in Auvers, a small village in the Haute Loire district.

.

Here is Père Fages’ story:

“Around the year 1799, there appeared in the country, especially around the village of Paliès, a beast that filled all the people immense fear; its size was slimmer than a wolf ; Its way of walking had such agility that it was seen in one place, and four or five minutes later it was seen in another place perhaps a league away. It had the head and muzzle of a large greyhound ; it used to come into villages in broad daylight, and woe betide any child that might meet the creature, the Beast would carry them off and eat them, first the liver and then the limbs. One summer’s day, the Beast appeared at Paliès. Children spied it from a long distance away and ran to take refuge in a tree close to a house on the northern side of the village; faster than lightning, the Beast seized one of the children, who was already two metres off the ground and carried him off into Madasse Wood. Men shearing the sheep of a local farmer, including the father of the unfortunate child, ran at top speed to the place where the Beast had gone. The noise that they made caused the Beast to abandon the little boy who was found shaking on the ground with his insides ripped out! Seeing his father looking for him, he did, however, have the strength, to shout “I’m here”, but he died a few moments later. This child aged six, was called Pierre-Jean Mauri; in the register Monsieur Arnal who carried out the baptism ceremonies in 1794 when the child was fifteen months old, has added to the margin of that register, “Devoured by the ferocious Beast”.

Fifteen days later, the Beast took a child from the farm of Graille at Rougerie. In company with his older brother, he was keeping watch over the cattle close to the natural spring of St. Martin; the elder brother tried hard to help his brother, but when the beast stood up on its hind legs, he was so frightened that he fled and went for help at Veyreau ; it was a Sunday, a large crowd came to help, and searching the Malbouche property, they found the remains of limbs that the Beast had hidden in the earth. This same beast also seized a little girl named Julien who lived in Bourjoie ; her father was busy knocking nuts down from the trees; the small children were close to the tree, and the Beast, in full view of the father, seized the little girl; the father set off after her, but he could not catch her up, and a few days later, she was found buried in the undergrowth; her liver had been eaten.

These different characteristics of the Beast filled the people of Veyreau and St André with justified fear; several people saw the Beast which accompanied them, gambolling along, jumping about, but not daring to attack adults; One day in bright sunshine, the Beast walked through the village of St André, and stopped outside the door of a weaver’s house; they took it for a dog, and at the very moment when they were going to stroke it, it disappeared in a flash. Monsieur Gaillard, the parish priest of St André, with whom I have discussed this extraordinary animal, assured me that he had heard it one evening in a small field below the duck pond, emitting howls like the braying of a donkey, something which was confirmed by several other people:All the local poachers met to hunt the creature, but when they encountered the Beast, they said that sometimes, especially when it was being shot at, the creature rolled around on the ground but then disappeared with enormous speed. The people who were children during this era, agree how great was the terror that it produced throughout the whole region of the “Black Causse”. Never attacking men or animals, because we had seen it pass through the middle of herds of cattle and flocks of sheep without doing them any harm, the Beast targeted only children. In the course of this year, from June to December, two boys and a girl were the sad victims of its ferocity; nobody dared walk outside on their own at night, and by day everyone carried a halberd at the end of a stick to defend themselves, in case they met the creature:

What was this Beast? It could not be classified as one of the known animals in the area; Monsieur Caussignac claimed that it was a hyena; Monsieur Gaillard, the village priest of St. André, thought it was a lynx, and the common people gave it the name of “Werewolf”, in French “Loup garou”:

After some six months or a year, the creature disappeared without anybody knowing what had happened to it. About the same time, a similar beast was seen in the Sanvero woods near the village of Cornus in the Aveyron province; it almost managed eat a little girl that I was to know twenty-five years later; she was near her home in the village of Labadie, in the parish of St Rome Berlières ; her brother, older than her, rushed to her defence and grabbed her from the creature, he dragged her into the house ; through the cracks in the closed door they could see the Beast watching and waiting for some time for the prey which had escaped, only by the skin of her teeth. Indeed, a bite from the creature had taken a considerable piece of skin from her side; this scar was never to fade throughout the rest of her life:

Whatever this animal was, its appearance had an enormous impact throughout the whole area of the Black Causse. Uneducated people saw in the Beast something supernatural, especially after all the upheavals and ordeals of the recent Revolution.”

And there you have it. Yet another wolf that seems to be not quite a wolf. At the moment, I am favouring the idea that up until about two hundred years or so ago, there was a second, much fiercer and larger species of wolf living in the remote and most mountainous areas of France, some prehistoric survivor that had lingered on until the nineteenth century in ever diminishing numbers, until, after tens of thousands of years, it finally became extinct. I cannot believe that the locals were incapable of recognising an ordinary wolf when they saw one. I cannot believe either that wolves were hybridising with dogs across the whole of France to produce killer hybrids. Wolves don’t have steamy affairs with dogs. They eat them!