I am still quite proud of the fact that I have found out so much information about the vast majority of these young men. I feel that I have done them all justice and that I have done my very best to keep them in people’s memories, even as they seem to be receding further and further into the anonymous grey mists of time. Here is the School Rugby team in 1926-1927:

I have made great efforts to drag the complete ghost out of the past and to write not just about their fiery deaths but to try and unfold the full and energetic lives they led. It’s only too easy to see a name on a war memorial, to read that name and then to forget it, all in the same moment. For that reason I have tried to describe their families, their fathers, their mothers, their brothers and sisters. I have tried to find out what their father did as a job, where the family lived, in some cases occupying just one or two houses in their lifetime, in others half a dozen. What were their houses like? How might they have travelled to the High School? I have tracked their Forms, their teachers, what they did at School, how their exams went, what position they came in class and what prizes they won, all the things that would have been so important to them at the time. I have written about what their Form Masters were like and talked about their careers. This is Mr Kennard. He definitely took no prisoners:

I have tried to find out what sports our future heroes played:

What school plays they were in. The French farce of the 1920s, “Dr Knock”, perhaps? And which one of these boys became the war hero?:

Or perhaps a play with a chance to wear a lovely frock and a string of pearls? :

Which person collected stamps and who loved to make home movies? I have tried to identify other boys in their Forms who might have been their friends, even if that is just a case of saying who won the Form Prize and where they lived, what job their father did and so on. Here is a class of really small boys, eight and nine year olds, before the First World War:

The worst thing I could have done would have been to have written three thousand words about their death and thirty about their lives. So whatever I could find, I have included. Their sports, their hobbies, their jobs between school and the forces, and, if possible, what their abilities and talents were.

By doing this I revealed, even to myself, just how many different places have provided High School pupils over these years and just how many hundreds of different jobs their fathers have done, some of them long gone and requiring a search on the Internet.

At least one High School hero of Bomber Command had come straight from Waring & Gillow’s shop to fly his Lancaster. He apparently said one day in the shop that selling double beds and three piece suites was not a worthy job for a man when his country was at war, and off he went. Waring & Gillow sold luxury furniture of all kinds, and they appear to have made a lot themselves, because here is their factory. :

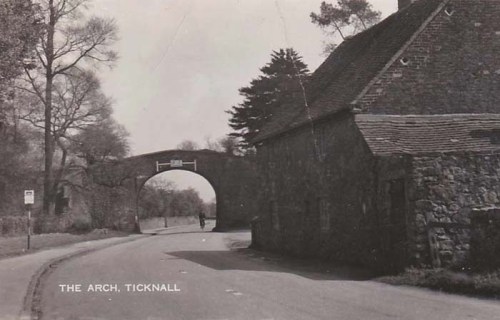

And when I have written about the boys’ streets and houses, some simple directions are usually included. Without them, which of us could ever locate Balfour Road or Conway Avenue or Derby Terrace or Florence Road? And many old streets have completely disappeared. This is a very different Forest Recreation Ground, only a few decades before the first of the World War Two casualties was born. Look at the windmills, and the race course for horses. It was one of the very few ever to be a figure-of-eight, in the hope of some juicy crashes:

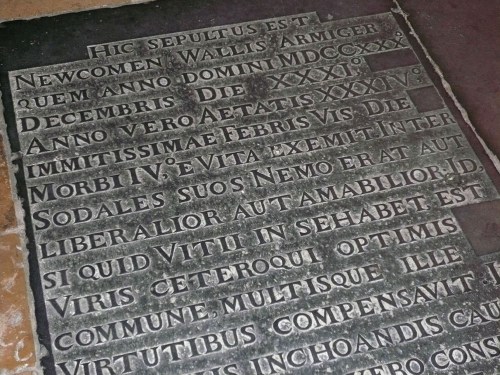

It is, of course, the young readers who are my ultimate target audience. It would be a tragedy indeed if they were never to realise who died for their right not to be brainwashed, not to speak German as their first language, not to be slave labourers in a foreign land and to have the right to make their own decisions at all the different stages of their young lives. Freedom does not come cheap, and I’m not talking about money. The situation is perhaps best summed up by what one Old Nottinghamian war hero has inscribed on his grave:

HE GAVE THE GREATEST GIFT OF ALL

HIS UNFINISHED LIFE.