Over the centuries, the weather can often be extreme, and some amazingly strange things have happened. In 1110, nearly a thousand years ago, Nottingham experienced a terrifying earthquake. Bizarrely, the River Trent dried up for several hours, presumably as it drained into, and then eventually filled up, a huge new crack in the ground that it had created somewhere upstream.

In the Nottingham of 1682, extremely low temperatures lasted from September until February of the next year. Shortages of coal, wood and food were caused by difficulties in the transport system, and the fields, roads and rivers were all frozen up. The Trent, for example, was completely impossible to navigate throughout the entire period of the freeze.

It was equally cold in 1855 when a cricket match was played on the frozen River Trent. The victors roasted, and ate, the greater part of a whole sheep without the ice either melting or giving way. When the thaw set in, an iceberg weighing many tons was unleashed in the river and it destroyed a bridge downstream when it crashed into it.

A local solicitor, William Parsons, recorded the weather’s outrages in his diary:

“In 1814, we had so severe a frost as to freeze the Trent over, the first time I believe. It continued 16 weeks. The Trent was then so frozen that a fair was held and oxen, sheep and pigs were roasted.”

In 1838, the River Trent froze over at the beginning of the year. William’s entry for January 20th reads:

“The frost has now continued about twelve days but with greater severity than is remembered. Many thousands from Nottingham went to see the Trent today. The frost continues extremely severe. The Trent this afternoon is now frozen completely over and I was sliding upon it just above Trent Bridge. I shall visit it tomorrow again it being of rare occurrence to be frozen. The snow continues upon the ground about six inches deep. My hands are very severely chapped that I am now writing in kid gloves”.

He described the river as:

“in that state frozen it appeared like a frothy, foaming river of snow. Many people were crossing on the ice. I walked down to the bridge and crossed the river just above it where numbers were also winding their way through projecting masses of snow covered in ice. The river was more rough and picturesque in this part than in any other.”

The most charming thing about William’s diary is his great honesty. As regards the consumption of alcohol in very large quantities, he was a man many years before his time:

“Time worse than wasted, money spent, health injured, myself debased! Let these days of drunken, senseless riot be remembered only as incitements to become a rigid teetotaller”.

We’ve all been there.

The River Trent was a very different river in those days and that is why it used to freeze fairly regularly during exceptionally cold weather. There were, of course, no power stations releasing huge quantities of warm water which might increase the natural temperature of the river, but that is not the most fundamental reason for the change. Nowadays, the waters of the Trent have been for the most part tamed and confined firmly in great ramparts of concrete. Because of the way in which the river has been turned into a giant canal, it is now much deeper and fast flowing than it used to be. The edges of the river do not extend outwards in leisurely fashion into marshes or shallow ponds with very little flow. The modern Trent no longer stretches, as it did in primeval times, from the sandstone cliffs south of St Mary’s Church for many, many hundreds of yards into present day West Bridgford. And the old wide river, of course, was a shallow, more slow flowing river, the kind of waterway that was much more likely to freeze in severe weather.

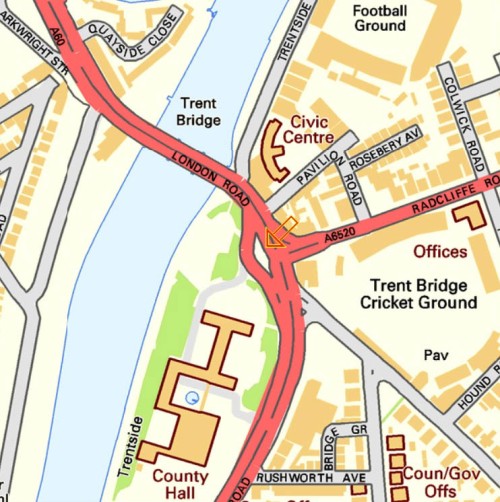

St Mary’s Church is in the top left of the map, near to the word “Museum”. It is represented by a cross and a square joined together. Trent Bridge is indicated by the orange arrow, and the southern edge of the waters centuries ago would have been well to the south of the present day B679 (bottom left of the map) or the Trent Valley Way (top middle right of the map).

In those ancient of days, when the river was so very much wider, the only safe crossing, either on foot or on horseback, was across the band of harder rock where Trent Bridge now stands.

On January 16th 1892, on a “piercingly cold” Saturday, Nottingham Forest played Newcastle East End at the City Ground. When the crowd arrived at Trent Bridge, they were surprised to see “skating in progress on the old course of the River Trent.” Because of the recent introduction of the penalty kick, the frozen football pitch had some new markings, which in this case were made of broad strips of black soot. Newcastle changed from their normal crimson shirts into black and white stripes. Hopefully, before the game, Old Nottinghamian Tinsley Lindley, Forest’s centre forward, was able to walk across the Trent to the game, just like Brian Clough used to do.

Three years later, in 1895, the river froze for the last time. Again, the region’s economy suffered. Numerous tributary rivers smaller than the Trent were also frozen, and many jetties and warehouses became unusable. This caused huge job losses in local industry.

The river was caught in this devastating frost for almost a fortnight. Skaters were able to venture onto the safe and solid ice over many miles of the Trent’s length. The ice was thick enough to allow a hockey game between teams from Newark and Burton-on-Trent to take place on a pitch somewhere upstream from Averham Weirs.

Here a huge crowd of boys are standing on the thick ice. Everybody looks very happy, but there were several fatalities, as people contrived to find excessively thin ice to stand on. Lady Bay Bridge can just be seen through the arches of Trent Bridge.

And not a scarf or a pair of gloves in sight. Kids were tough, and Health and Safety hadn’t even been thought of yet.

The photograph above was taken from opposite the West Bridgford embankment, to the south of Trent Bridge, near to the present day County Hall. Look for the orange arrow:

In places the extreme frost, the most severe in living memory, penetrated into the ground so deeply that it froze the tap water in the mains. Ordinary people suffered greatly and many had no water supply whatsoever, a parlous situation which was to last for several weeks. To overcome this most basic of problems, stand-pipes fitted with taps were set up at various places in the streets, and buckets could be filled up there. January and February of 1895 was a time of difficulty and danger for ordinary people and those who survived it were to remember it for the rest of their lives.

In the photograph above, a fire can be seen burning against the bridge, one of the many which blazed happily on the surface of the ice. The river’s rate of flow is reduced by the ice floes so much that it is almost reminiscent of a river during a drought.

During these bitterly cold winters at the turn of the twentieth century, my grandfather, Will, who had emigrated to Canada around 1905, saw Niagara Falls, for the large part frozen, on at least one occasion, this postcard dating most probably from 1911.