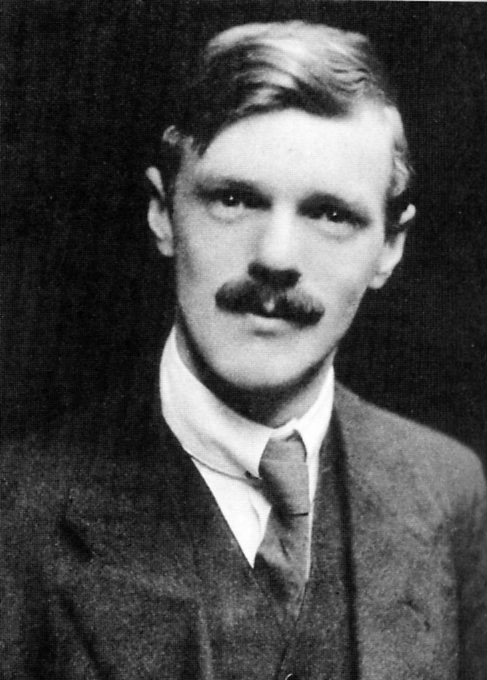

I have previously written two articles about Frank Mahin. The first recounted how he had carved his name on a stone fireplace in the High School:

The second article had a title very similar to this one, but it was entitiled The Incredible Story of Frank Mahin, Volume I, 1887-1909

And now, Dear Reader, my tale continues:

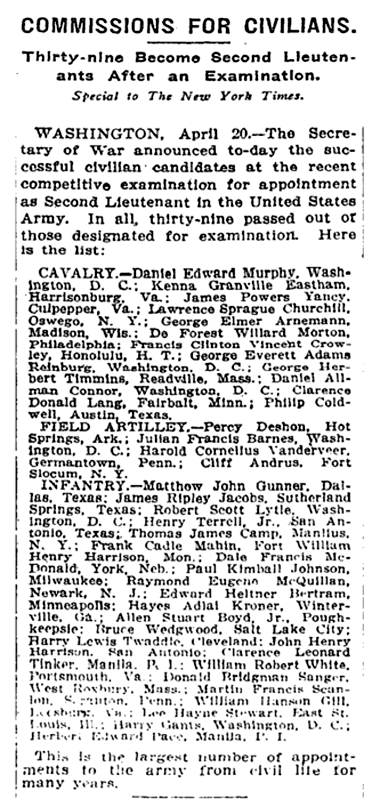

Frank Cadle Mahin was so keen on a military career, that after only two years, he left Harvard University and his boring Law studies. He joined the Regular Army in 1910 as a private soldier, after service with the New York National Guard. Two years later he received his first commission. On April 21st 1912, Mahin and thirty eight others took an examination and were all made Second Lieutenants:

At this time, Frank is listed as being at Fort William Henry Harrison in Montana.

On September 25th 1913, Frank was married to Margaret Mauree Pickering, his previous, second, marriage to Sasie Avice Seon having, presumably, come to an end in some way. Again, unfortunately, the precise details are lacking.

Margaret Mauree was born in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, USA in 1890, the daughter of Abner Pickering and Celestia Florence Kuykendall. In married life she was to call herself Mauree Pickering Mahin so that her father’s name was never forgotten. Her father, and Frank’s father-in-law, was Abner Pickering, who came from a very strong military background, as is shown by the wedding announcement in a local newspaper:

In her book, “Life in the American Army from the Frontier Days to Army Distaff Hall”, Mauree describes the magic moment when she first met her future husband:

“We sat down, and the place next to me was left vacant for him. When he did

arrive, everyone forgot that we had not met, so after a minute of awkward

silence he took the vacant seat saying: “I guess no one is going to introduce us, I am Lieutenant Mahin, and I am sure you are Miss Pickering.”

With that one look into his clear steady eyes, I was convinced that there was such a thing as “Love at First Sight” and that I was not going to let the blonde or anyone else have him.”

Frank and Mauree were to have four children, including twins named Margaret Celestia and Anna Yetive, both born on June 2nd 1915 in the Philippines which at the time was an American colony, seized from the Spanish after the Spanish-American War. Frank’s three daughters were all to marry, as was his son, Frank junior, bom in Connecticut on January 2nd 1923. His third daughter, Elizabeth, lived from 1921-1981 and Frank junior, like his father, was a distinguished military man until he died in Dallas, Texas, on January 28th 1972.

.

In November and December 1914 Frank and the regiment received extremely unexpected orders. They were to go to Naco in Arizona where Pancho Villa. the legendary Mexican bandit, and the inventor of the moustache, was up to his tricks, causing trouble:

The American garrison was tasked with keeping Villa’s men from crossing the Mexican border into the USA. Orders from Washington stipulated though, that, in the interest of preserving friendly international relations, no shots were to be fired, even if the bandits fired at them, a rather difficult policy to carry out!

That was December 1914. Europe had already been at war since August, and more than a million young men were already dead. Frank Cadle Mahin, as you will see in another article, was to play his part in this sickening slaughter.

In early 1915, Frank was sent to the Philippines, then still an American colony. Here he was to have an unexpected chance to practice the German he had learned at the High School. Let’s not forget that in 1905, he had won the Mayor’s Prize for Modern Languages:

“On to Guam our next port of call, and there the war was brought directly to our minds, for anchored in the harbour was one of the converted German warships, riding at anchor. She had been forced in there by lack of coal and, of course, was interned for the duration of the war! Our Quartermaster had occasion to visit this ship with some supplies, and since he spoke no German, he asked Frank to go with him and interpret for him. Judging by the time they were gone, it must have been an interesting and pleasant afternoon. One thing I do know, the Germans may have run out of coal, but not out of good German beer!”

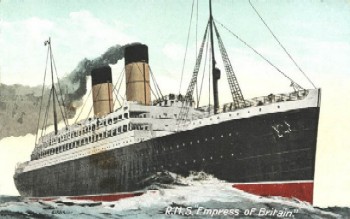

The first Mahin to be seriously affected by the Great War was Frank Senior. At this time, he, and his wife, Abbie, were, of course, both citizens of a neutral United States. In September 1915 they made the ferry crossing from Holland, where, by now, Frank Senior was the American consul in Amsterdam. They were on their way to visit their daughter, Anna and her doctor husband Alec in Nottingham, England:

“The journey is made by daylight during the war so we sailed from Flushing at 6.00 am. on July 31st on the Dutch liner Koiningin Wilhelmina. The day was lovely and the sea calm, and all was calm and restful till ten minutes before ten, when, a sharp explosion beneath us was heard, and great volumes of water blew up over the sides of the ship. Passengers on the forward deck, under which the explosion occurred, were drenched with water and covered with black particles, which came from the mine which, as we all

realized, the ship had struck:

As the explosion was under the stoke-hold three poor stokers were killed, and one fatally wounded. We put on overcoats, hats, and lifebelts and went on deck. In about ten minutes all of the lifeboats had been loaded and left the ship. The boats rowed toward the lightship, about three miles distant. As we left the ship, the forward part was slowly sinking. But in half an hour the boat sagged in the middle. That part sank out of sight, and the bow and stern rose straight in the air. From the stern floated the Dutch flag, thus the two ends stood for some minutes. Then they came together as one: the flag floating from the top of it. Slowly that column disappeared under the water at fifteen minutes before eleven o’clock, fifty-five minutes after the mine was struck.

Scattered about were our lifeboats rowing towards the lightship, which was a mile or two away. Beyond it, cruising swiftly in circles, was the British war vessel which afterwards took us to England. Behind us was the sinking ship, whose last moments were like the despairing struggle of some living thing; and we thought of the poor dead men who were going down with the ship, as might have been the fate of all of us.

At the same time we heard the roar of cannon in the direction of Belgium, adding more death and destruction to this awful war. All the boats reached the lightships safely by noon, and everyone was safe. About six that evening a British torpedo boat destroyer took us to Harwich, England, where we arrived at 8:30 that night. We spent the night at Harwich, and at midnight we heard the sound of bombs exploding, Zeppelins being in the vicinity.

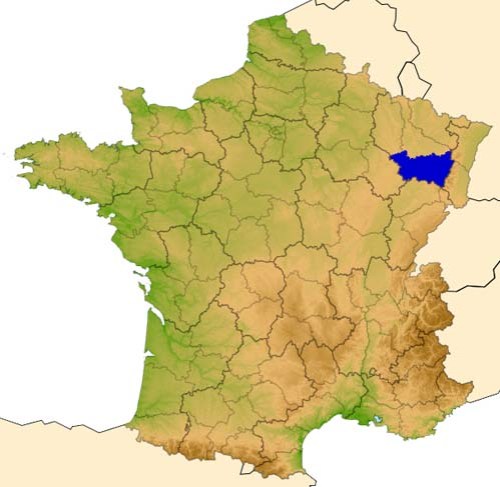

Frank junior had been swiftly promoted following his good work against Pancho Villa and his band of Mexican bandits. He became a Major just in time for the USA’s entry into the Great War, and served in combat in France in 1918. He was wounded at St. Mihiel, the first time that American troops were in really significant action, as they launched an offensive against retreating German forces. Frank was to win a Purple Heart, showing great bravery under enemy fire:

Frank then went on to fight in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and the Battle of the Argonne Forest. He had at least one amazing escape:

“I think I am more than lucky to be here at all. I have had narrow escapes before, since

I came over to France, but had more in this day and a half in the Argonne than all the rest put together. For instance, Hancock, my liaison officer, and I were lying in a shell hole with machine gun bullets cutting the top edges off and knocking the dirt all over us. Then a 105mm artillery shell hit right at the edge of the hole and slid down under us, raising the ground up, like a mole furrows, on the side of the shell hole.Of course it was sliding for the tiniest part of a second but we heard it, felt it, and knew what it was, and then it burst! Good night! In that fraction of a second, I thought “God bless my girls, “ but we weren’t hurt! It was a gas shell, thank God, with just enough explosives to crack the case and throw the dirt around. We had our masks on anyway, so it did not harm us, but Hancock looked like a ghost, and fool that I am, I laughed at him and took my mouthpiece out and yelled, “ Going up!” and even he had to smile then! Had that shell been a High Explosive they would never have found even our identification tags. If it had been even an ordinary gas shell, half gas and half High Explosive, it would’ve blown both of us to pieces.”

In the 1920s, when he returned to the United States, Frank, still fresh faced and eager, was to relate to his twin daughters exactly what his life under fire had been like:

“The trouble is gas, we were in it almost continuously for three hours, and I tried to keep my mask on, but you just can’t run a battalion in battle with a gas mask on. It was a wet, misty morning when we went “over the top” and they just poured gas shells over, tear gas, sneezing gas, then phosgene and mustard after they had gotten our noses and eyes inflamed.

The country was the worst possible country to fight over, for it was just ridge after ridge with fire coming at us from every direction. Believe me, it was some scrap. Saint Mihiel was a cinch compared to this Argonne Forest offensive.

From the Field Hospital, they sent me by truck to Evacuation Hospital No 7. I stayed there a day and a half, and then to Base Hospital No 27, a Pittsburgh outfit at Angers near the mouth of the River Loire. The hospital is in a big old three-storey convent building, and is awfully comfortable, and the ‘chow’ is fine.

Nausea, acute diarrhea, for several days, and an awful headache, all from the gas, and, of course, burning lungs. I now feel pretty good but the d— stuff has affected my heart. They say this does not last more than a week if one stays perfectly quiet, but for several more weeks I will have to be very careful not to exert myself violently.”

His wife Mauree, however, adds a little more realism to the tale, pointing out just how seriously affected her husband was:

“I can assure you, girls, that that heart condition lasted several years instead of several weeks. Even after his return, and for many months, he would be sitting talking, and without warning would fall right out of the chair, and I never knew when we picked him up whether he would be dead or alive.”

Nowadays we have little or no idea of what it must have been like in the trenches during a gas attack:

We are given some idea, however, when the family take a trip to a more peaceful Europe in 1920. It is Frank’s wife, Mauree, who tells the tale:

“On this trip we followed the movements of the 11th Infantry up to the time of Dad’s gassing and evacuation. At Madeleine Farms, where his battalion command post was during one of the offensives, we were able to go down into the very dugout he had used! It had two entrances, and both were completely overgrown with vines. As Dad and I started down the rickety old rotted-out steps, Dad recognised the odor of gas still down there, and he whispered to me not to tarry long but just to take a quick look and go out of the other entrance. The dampness was terrible, water dripping off of the low ceiling, we were able to see the boards hung against the side where they slept when there was a minute to spare, and we actually walked on the duckboard.

As quickly as we went through, Dad was greatly affected by that little gas, and had a very hard attack of coughing ; and just as we got into the car Grandma had a heart attack, and this was two whole years after the war , thus you can see, just how potent that gas really was!

Here are the Madeleine Farms, then and now, as it were:

In my next article about Frank, I will tell the tale of how he continues his military career and eventually achieves a very high rank in the American army.