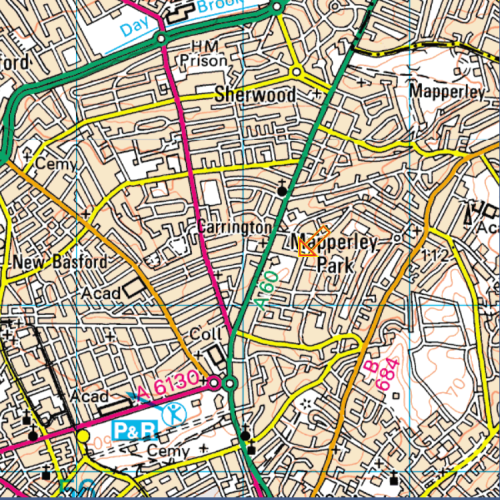

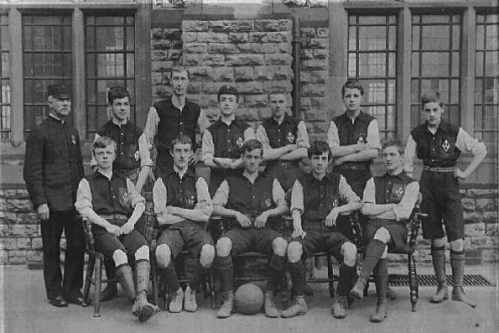

This photograph shows the First Team in the 1904-1905 season. It was taken at Mapperley Park Sports Ground, opposite the old Carrington Lido on Mansfield Road.

Sergeant Holmes is again present, and the players are….

(back row) S.D.M.Horner, C.F.R.Fryer, M.J.Hogan, R.E.Trease and J.P.K.Groves

(seated) R.G.Cairns, R.B.Wray, R.Cooper (Captain) and L.W.Peters

(seated on grass) H.E.Mills and P.G.Richards

On the right is twelfth man, F.C.Mahin. You can read about the incredible life of Frank Cadle Mahin in three of my previous blog posts.

I believe that the photograph was taken on the afternoon of Wednesday, October 12th 1904, just before the High School played against Mr.Hughes’ XI, perhaps to commemorate the game for the old Drill Sergeant. The School won 12-5, and we know that Cooper in defence was the outstanding player, but the whole team played well, and the forwards’ finishing was particularly deadly. This year, the team was amazingly successful. Their season began with victories by 5-4, 2-1, 23-0, 12-5, 9-0, 15-0, 3-1, 4-1, 11-0, 16-1. They had scored exactly 100 goals by November 3rd, in only ten games.

Notice that it is warm enough for the changing room windows to be open, and the design of the ball is still that old fashioned “Terry’s Chocolate Orange”. Horner has forgotten his football socks, and, because this game marked his début for the side, Fryer’s mother has not yet had the time to sew his school badge onto his shirt. Frank Mahin is, in actual fact, in the full School uniform of the time…a respectable suit or jacket, topped with a Sixth Form white straw boater, with a school ribbon around it. Here he is in American military uniform:

Football, though always, seems to have appealed to the rebellious nature of the boys. Even when it was a school sport, some of them wanted more, and they were quite prepared to break the rules of the High School to achieve that aim. The Prefects’ Book records how “an extraordinary meeting of the Prefects was held after morning school on November 23rd 1908”.

AB Jordan reported that a Master, Mr WT “Nipper” Ryles…

“… had complained about a cutting in the “Football Post” & “Nottingham

Journal”, stating that the High School had been beaten 5-1 by some unknown team called Notts Juniors, reported 8 boys out of IIIC, 1 out of IIIB, 1 out of IVB. The boys were Davie (J.R.), Herrick (R.L.W.), Gant (H.G.) Hemsley, Major, Parrott, Wilmot, Tyler, Cowlishaw & Sadler. They had played against a team of Board School boys down at Bridgford, under the name of Nottm High School Third Form. The other team had put the result in the paper. They were told that such teams must not be played, & that nothing must be sent to the papers except the results of 1st XI & 2nd XI matches. Signed AB Jordan”.

The School Archives also have a photograph of older boys in an unknown team. Nobody has any real, definite and provable idea about who they might be. Perhaps they were something unofficial too:

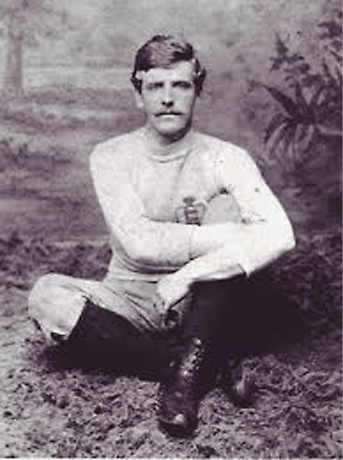

The man behind the team is not a known member of staff. Here he is:

Is the mystery man is one of Haig’s staff officers from 1914, on an early lookout for likely cannon fodder for the Western Front? Why should I think that? Well, take a look at this photograph of a group of what were probably the cleverest, shrewdest military thinkers of their age, “Field Marshal Haig and the Blockheads”. Perhaps, front left, Tubby Watson? :

The next team photograph is not one I am particularly proud of. It is the sad result of the practise of using a camera to scan images because it is so much quicker. It appeared in the School Magazine a few years ago and they seemed to have little knowledge of who it is:

The caption reads

“Is the above photograph a School Football Team of the early 1890s? The only proof that the team is the three merles badge on the shirt of one of the boys. The photograph is supplied by Don E Stocker (1926-1932) and his father EB Stocker (1889-1891). Is the man on the right a master or possibly Mr Onions, the groundsman and cricket coach?

Well, he’s neither a Master nor Mr Onions in my opinion:

And the badge may mean it is a High School team but not 100% definitely. It might be the only football shirt he has:

And surely, if it was a High School football team, more than one would be wearing a proper football shirt. As far as I can see, the majority of the players are wearing ordinary white shirts such as they might wear in the bank where they worked, or the technical drawing office.

I don’t think the team is pre-1900 either because the ball is made of 18 panels sewed together. Balls from this period tended to be like a Terry’s Chocolate Orange with lots of segments held in place by a circular piece of leather on either side. It may be a renegade team though, because School football stopped in 1914 and this photograph may well date from after that.

More Ché Guevarras of High School football next time.